Validating Evolutionary Predictions in Viral Evolution: From Forecasting Variants to Designing Future-Proof Therapies

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methods, applications, and validation frameworks for predicting viral evolution, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Validating Evolutionary Predictions in Viral Evolution: From Forecasting Variants to Designing Future-Proof Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methods, applications, and validation frameworks for predicting viral evolution, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles that make viruses predictable, detailing the drivers of antigenic change and immune evasion. The review covers a suite of methodological approaches, from integrative fitness models combining genetic and epidemiological data to AI-powered frameworks like EVEscape and machine learning for antiviral discovery. We address critical challenges in forecasting, including epistasis and eco-evolutionary feedback, and present optimization strategies. Finally, we establish a rigorous framework for validating predictions, comparing computational and experimental techniques, and assessing their real-world impact on pre-emptive vaccine strain selection and the design of mutation-resistant drugs.

The Science of Forecasting Viruses: Why Viral Evolution is Predictable

For researchers and drug development professionals, the ability to accurately predict viral evolution is a critical frontier in public health. The rapid emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants and the persistent evolution of influenza viruses underscore that viral pathogens are moving targets, constantly adapting under selective pressures. This evolutionary arms race necessitates robust methods for forecasting viral trajectories. At the core of this adaptation lie two fundamental drivers: immune pressure that selects for antigenic escape and functional trade-offs that constrain evolutionary pathways. This review compares contemporary approaches for validating evolutionary predictions, examining how different methodologies capture the interplay between immune evasion and replicative fitness. We evaluate the experimental protocols, data requirements, and predictive performance of competing frameworks—from theoretical models to machine learning applications—providing a systematic comparison of their capabilities for anticipating viral evolution.

Theoretical Foundations: Trade-Offs and Population Immunity

The conceptual foundation for viral evolution prediction rests on understanding how selective pressures shape viral trajectories. Research indicates that viral evolution is not unbounded but is constrained by a fundamental trade-off between immune evasion and transmissibility [1]. Models incorporating this trade-off reveal that when highly transmissible strains dominate, natural selection favors immune evasion, whereas less contagious strains evolve toward increased transmissibility [1]. This dynamic creates predictable evolutionary patterns, including convergence, periodic oscillations between strain types, and under certain conditions, chaotic regimes that defy long-term prediction [1].

At the population level, the balance between these selective forces depends critically on the host immune landscape. Analytical frameworks show that the relative fitness advantage of an immune-escape variant over a transmissibility variant occurs when past exposure levels exceed a critical threshold, defined as φ* = Ï/(η+Ï), where Ï represents the proportional increase in transmissibility and η represents the escape proportion against wildtype immunity [2]. This relationship demonstrates that as population immunity grows, immune escape inevitably becomes the dominant mechanism for variant success [2].

Table 1: Key Evolutionary Drivers and Predictable Patterns

| Evolutionary Driver | Impact on Viral Evolution | Resulting Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Host Immune Pressure | Selects for mutations enabling escape from neutralizing antibodies | Accelerated nonsynonymous substitution rates; parallel evolution across hosts [3] |

| Transmissibility-Immune Evasion Trade-off | Constrains evolutionary pathways; prevents simultaneous optimization of both traits | Cyclical strain replacement or convergence to stable transmissibility level [1] |

| Within-Host Diversity | Enables rapid adaptation during prolonged infections | Co-circulating viral lineages within single hosts; heterogeneous antigenic evolution [3] |

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Approaches

Theoretical Modeling and Simulation

Experimental Protocol: Theoretical approaches begin with constructing fitness landscape models that incorporate different genomic sites: synonymous (neutral), phenotypic (impacting replicative fitness), antigenic (impacting immune recognition), and pleiotropic (impacting both) [3]. Using the Rough Mount Fuji model, researchers simulate viral evolution by quantifying replicative fitness through the equation: f(g) = -cd(g, r) + ε, where c is a landscape ruggedness parameter, d(g,r) is the Hamming distance from a reference genotype, and ε is a random variable introducing epistasis [3]. Simulations introduce immune pressure by modeling host immunity as a factor reducing infection probability for antigenically similar strains.

Supporting Evidence: Simulation studies demonstrate that replicative fitness landscapes alone cannot explain observed within-host evolution patterns, including accelerated nonsynonymous substitutions and parallel evolution across individuals [3]. The consistent emergence of these patterns requires incorporating immune pressure, with stronger immune responses and intermediate immune breadth generating the greatest antigenic change [3].

Data-Driven Fitness Estimation

Experimental Protocol: Data-driven approaches leverage large-scale genomic surveillance to estimate variant fitness in real-time. The standard protocol involves: (1) collating high-quality viral sequences from repositories (GISAID/GenBank), excluding sequences with >1% ambiguous characters or incomplete dates [4]; (2) aligning sequences using tools like MAFFT; (3) constructing timed genealogical trees; (4) estimating variant frequencies over time; and (5) applying multinomial logistic models to calculate relative effective reproduction numbers (Re) between variants [5]. More advanced implementations use Gaussian processes with Hilbert Space approximations to model time-varying fitness without assuming constant selective advantages [2].

Supporting Evidence: This framework successfully tracked the fitness transition in SARS-CoV-2 from transmissibility-driven (Alpha, Delta) to immune escape-driven (Omicron lineages) success as population immunity increased [2]. The method provides an early growth signal using genetic data alone, crucial in scenarios with case underreporting [2].

Protein Language Models (AI-Based Prediction)

Experimental Protocol: The CoVFit model exemplifies the AI-based approach, adapting the ESM-2 protein language model specifically for SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prediction [5]. The protocol involves: (1) domain adaptation through additional pretraining on Coronaviridae spike proteins; (2) multitask fine-tuning using both genotype-fitness data (from surveillance) and deep mutational scanning (DMS) data on antibody escape; (3) embedding generation for spike protein sequences; and (4) fitness regression based on these embeddings [5]. This model can predict variant fitness from a single spike protein sequence, without requiring accumulation of epidemiological data.

Supporting Evidence: CoVFit achieved remarkable predictive performance, with Spearman's correlation of 0.990 for ranking variant fitness in validation tests [5]. The model identified 959 fitness elevation events throughout SARS-CoV-2 evolution and successfully forecasted the fitness of variants harboring nearly 15 mutations not seen during training [5].

Deep Mutational Scanning and Antibody Selection

Experimental Protocol: Experimental approaches use deep mutational scanning (DMS) to prospectively identify broadly neutralizing antibodies. The method involves: (1) creating comprehensive mutant libraries covering key viral proteins (e.g., receptor-binding domain); (2) performing high-throughput neutralization assays with monoclonal antibodies; (3) integrating escape profiles with codon preferences, ACE2 binding data, and structural constraints to predict mutation hotspots; (4) designing pseudoviruses encoding predicted escape mutations; and (5) screening candidate antibodies against these prospective variants [6].

Supporting Evidence: In a retrospective analysis of 1,103 SARS-CoV-2 wild-type-elicited monoclonal antibodies, this approach increased the probability of identifying antibodies effective against the XBB.1.5 variant from 1% to 40% [6]. Antibodies identified through this method, such as BD55-1205, demonstrated potent neutralization against all tested variants, including highly evasive strains like JN.1 [6].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Predictive Methodologies

| Methodology | Prediction Horizon | Data Requirements | Key Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Modeling | Long-term (cyclic/chaotic regimes) | Population immunity estimates, trade-off parameters | Identifies evolutionary regimes; explains heterogeneous antigenic evolution [1] [3] | Qualitative rather than strain-specific predictions |

| Data-Driven Fitness Estimation | Short-to-medium term (weeks-months) | Temporal variant frequency data from genomic surveillance | Estimates time-varying relative fitness; identifies emerging variants 7-28 days earlier [2] [5] | Requires sufficient sequence accumulation; lag in detecting new variants |

| Protein Language Models | Immediate (on sequence availability) | Spike protein sequences; historical fitness data | Spearman's correlation: 0.990; predicts fitness of unseen mutations [5] | Black-box nature; limited interpretability of epistatic interactions |

| Deep Mutational Scanning | Medium-term (prospective variant design) | Mutation-antibody escape profiles; structural constraints | Increases bnAb identification rate from 1% to 40% [6] | Resource-intensive; limited to predefined mutation space |

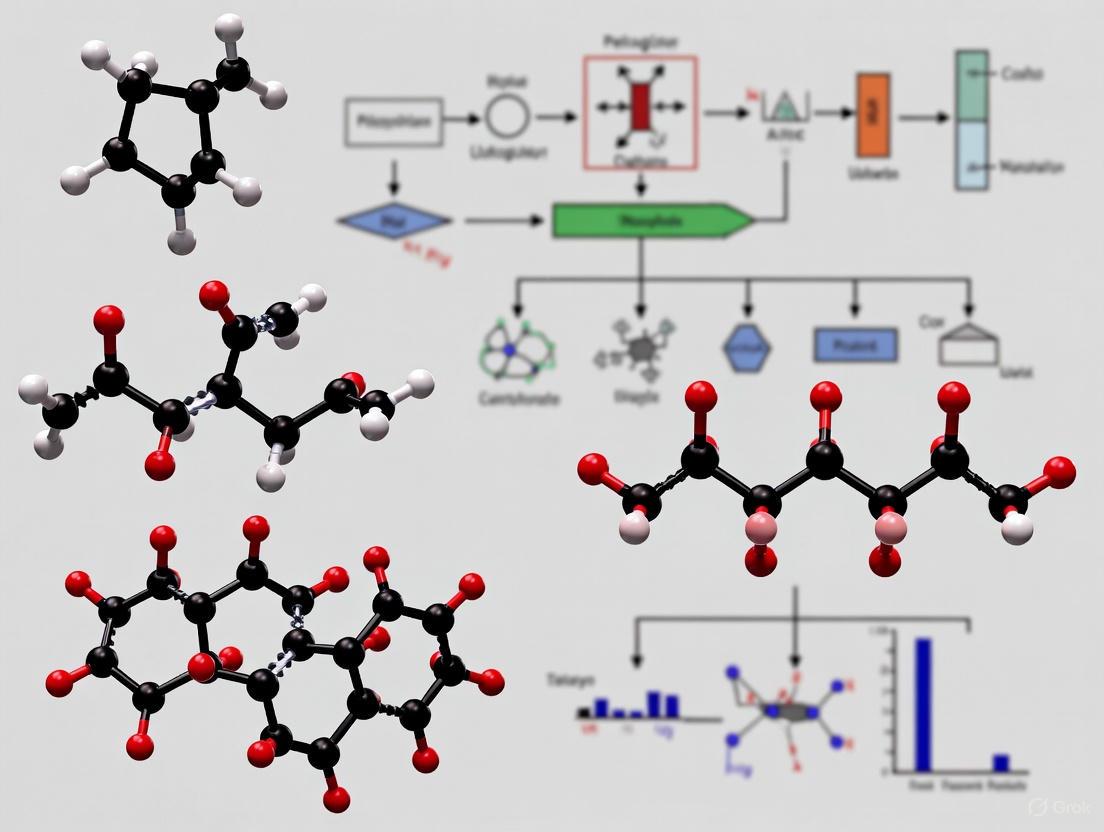

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between evolutionary drivers, predictive approaches, and their applications in public health and drug development:

Figure 1: Logical framework connecting evolutionary drivers to predictive applications

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Mutational Scanning Libraries | Comprehensive mutant libraries for high-throughput phenotyping | Mapping antibody escape potential and fitness effects of mutations [6] |

| Monoclonal Antibody Panels | Tools for assessing neutralization breadth and escape profiles | Screening candidate therapeutic antibodies against prospective variants [6] |

| Pseudovirus Systems | Safe surrogate models for neutralization assays | Evaluating antibody efficacy against current and designed future variants [6] |

| ESM-2 Protein Language Model | Protein sequence embedding and fitness prediction | Predicting variant fitness from spike protein sequences alone [5] |

| GISAID/GenBank Sequences | Curated viral genomic data | Training data for fitness models and evolutionary tracking [4] [5] |

| Antigenic Assays (HI/Neutralization) | Quantitative measurement of antigenic distances | Constructing antigenic maps and measuring immune escape [4] |

The validation of evolutionary predictions in viral evolution research requires complementary approaches that address different aspects of the prediction problem. Theoretical models provide the conceptual framework for understanding long-term evolutionary dynamics and regime shifts, while data-driven methods offer real-time tracking of variant fitness in changing immune landscapes. Machine learning approaches, particularly protein language models, enable immediate fitness prediction from sequence data alone, potentially overcoming the surveillance lag time. Finally, experimental methods using deep mutational scanning provide a mechanistic basis for selecting broadly neutralizing therapeutics that resist future escape. The integration of these approaches—combining theoretical insights, population-level surveillance, artificial intelligence, and experimental validation—creates a robust framework for anticipating viral evolution and developing durable countermeasures. As these methodologies continue to mature, their synergistic application will be essential for staying ahead of the evolutionary curve in pandemic preparedness and response.

Understanding viral evolution requires integrating concepts from evolutionary biology, genetics, and virology. Antigenic drift and epistasis represent two fundamental evolutionary forces that shape how viruses adapt to host immune systems and environmental pressures. While antigenic drift describes the gradual accumulation of mutations in antigenic sites, epistasis reveals how genetic interactions influence evolutionary trajectories. Together, these concepts help researchers map the evolutionary landscapes that determine viral fitness and predict future variant emergence. This guide compares how these distinct but interconnected evolutionary mechanisms operate across different viral systems and research methodologies, providing a framework for developing more accurate evolutionary prediction models in virology and drug development.

The study of viral evolution has been revolutionized by large-scale genomic sequencing and sophisticated fitness landscape models. Recent research demonstrates that despite the apparent unpredictability of individual mutations, global statistical patterns emerge that can inform prediction strategies [7] [8]. For respiratory viruses like influenza and SARS-CoV-2, these evolutionary concepts have direct implications for vaccine design and therapeutic development, as understanding the rules governing antigenic change and genetic interactions enables more proactive responses to viral adaptation.

Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

Antigenic Drift: Continuous Viral Adaptation

Antigenic drift refers to the gradual accumulation of mutations in viral surface proteins, specifically in the antigenic sites recognized by host immune systems. This process occurs through small genetic changes during viral replication and results in viruses that are closely related but antigenically distinct over time [9]. For influenza viruses, antigenic drift primarily affects the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) surface proteins [10]. The evolutionary significance of antigenic drift lies in its role in enabling viral immune evasion, necessitating regular updates to vaccine formulations. Recent examples include the H3N2 subclade K variant, which emerged through antigenic drift after vaccine strain selection for the 2025-26 season, creating a potential mismatch between circulating strains and vaccine protection [11].

The molecular mechanism underlying antigenic drift involves point mutations in genes encoding viral surface proteins. These mutations occur due to the error-prone nature of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, which lack proofreading capabilities. When mutations occur in antigenic sites—specific regions targeted by neutralizing antibodies—they can reduce antibody binding affinity, allowing variants to partially escape pre-existing immunity [9] [10]. This process creates selective advantage for strains with mutations that diminish immune recognition while maintaining viral fitness, driving continuous viral evolution in human populations.

Epistasis: Genetic Interactions Shape Evolutionary Paths

Epistasis describes the phenomenon where the effect of a genetic mutation depends on the genetic background in which it occurs [7]. In viral evolution, epistasis manifests when the fitness effect of a mutation changes depending on other mutations present in the viral genome. Recent research has revealed that epistasis can be "idiosyncratic" (specific to particular mutations and their biological interactions) or "global" (following systematic patterns correlated with background fitness) [8]. The evolutionary constraint imposed by epistasis significantly influences which mutational pathways are accessible to viruses, creating historical contingency that can make evolutionary outcomes more predictable.

Studies of the folA fitness landscape in E. coli demonstrated the "fluid" nature of epistasis, where the type of epistasis between two mutations changes dramatically across different genetic backgrounds [7]. This fluidity creates complex evolutionary landscapes with multiple fitness peaks and valleys. Similarly, research in budding yeast showed that global fitness-correlated trends (such as diminishing returns epistasis, where beneficial mutations have smaller effects in fitter backgrounds) can emerge from underlying idiosyncratic genetic interactions [8]. This hierarchical structure of epistasis has profound implications for predicting viral evolution, as it suggests that while specific mutations may have unpredictable effects, overall trends may follow discernible patterns.

Evolutionary Landscapes: Mapping Genotype to Fitness

Evolutionary landscapes (or fitness landscapes) represent the mapping between genetic sequences and their corresponding fitness in specific environments [7]. These multidimensional surfaces determine how easily populations can evolve from lower-fitness to higher-fitness genotypes. The "ruggedness" of a landscape—determined by the prevalence and strength of epistatic interactions—influences evolutionary predictability and navigability [7]. Rugged landscapes with many epistatic interactions contain numerous local fitness peaks that can trap evolving populations, while smoother landscapes allow more direct access to global fitness maxima.

Table 1: Characteristics of Different Evolutionary Landscape Types

| Landscape Type | Epistasis Pattern | Evolutionary Predictability | Real-World Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smooth Landscape | Minimal epistasis | High predictability | Early SARS-CoV-2 D614G variant |

| Rugged Landscape | Strong idiosyncratic epistasis | Low predictability | Influenza HA stem region |

| Terraced Landscape | Global diminishing returns | Moderate predictability | SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants |

| Fluid Landscape | Context-dependent epistasis | Variable predictability | folA gene in E. coli [7] |

Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Mechanisms

Temporal Patterns and Evolutionary Rates

Antigenic drift and epistasis operate on different timescales and exhibit distinct temporal dynamics. Antigenic drift represents a continuous, gradual process that occurs steadily over time as viruses replicate in host populations. This constant mutation accumulation leads to relatively predictable seasonal strain replacements in viruses like influenza, with noticeable antigenic changes typically occurring over 2-5 year cycles [11]. In contrast, epistatic interactions can produce both gradual and abrupt changes in evolutionary trajectories depending on the genetic background. The "fluid" nature of epistasis means that the evolutionary effect of a mutation can change instantaneously when other mutations appear in the genome, creating potential for rapid fitness shifts [7].

The different temporal patterns of these evolutionary mechanisms directly impact their roles in vaccine efficacy and therapeutic resistance. Antigenic drift consistently erodes vaccine effectiveness through steady accumulation of mutations in antigenic sites, necessitating regular vaccine updates. For influenza, vaccine effectiveness typically declines over a single season as drifted variants emerge [11]. Epistasis, however, can cause unexpected failures when particular mutation combinations create variants with disproportionate fitness advantages or resistance profiles. The Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, with its extensive constellation of mutations, exemplifies how epistatic interactions can generate variants with significantly altered antigenic properties [12].

Predictability in Evolutionary Forecasting

A crucial distinction between antigenic drift and epistasis lies in their predictability for evolutionary forecasting. Antigenic drift shows moderate predictability based on historical mutation patterns and selective pressures. Influenza surveillance programs successfully identify emerging drifted variants by monitoring mutation accumulation in circulating strains [11]. However, epistasis introduces significant challenges for prediction because mutation effects are context-dependent. Research on the folA landscape revealed that epistasis between mutation pairs can switch between positive, negative, and sign epistasis across different genetic backgrounds, creating evolutionary unpredictability [7].

Despite these challenges, recent advances in protein language models and deep mutational scanning have improved predictions of epistatic effects. The CoVFit model, built on the ESM-2 protein language model, successfully predicts SARS-CoV-2 variant fitness from spike protein sequences by leveraging both genotype-fitness relationships and functional mutation effects [13]. This approach demonstrates how machine learning can capture complex epistatic interactions to forecast viral evolution. Similarly, genome-wide fitness landscapes in yeast have revealed that global epistatic patterns can emerge from underlying idiosyncratic interactions, providing a statistical framework for predicting evolutionary trends despite specific unpredictable interactions [8].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Antigenic Drift vs. Epistasis in Viral Evolution

| Characteristic | Antigenic Drift | Epistasis |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Basis | Point mutations in antigenic sites | Interactions between mutations |

| Evolutionary Timescale | Gradual (seasonal) | Variable (instant to gradual) |

| Impact on Vaccines | Steady efficacy decline | Potential for abrupt efficacy loss |

| Predictability | Moderate based on surveillance | Low to moderate with advanced models |

| Research Methods | Genomic surveillance, serology | Fitness landscapes, DMS, protein modeling |

| Therapeutic Implications | Annual vaccine updates | Combinatorial therapy design |

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Studying Antigenic Drift: Surveillance and Serology

Research on antigenic drift employs distinct methodological approaches centered on genomic surveillance and serological testing. The primary protocol for monitoring antigenic drift involves collecting viral samples from clinical cases, sequencing hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) genes, and comparing them to vaccine strains [11]. The specific workflow includes: (1) sample collection from surveillance networks, (2) RNA extraction and sequencing, (3) phylogenetic analysis to identify emerging lineages, (4) hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assays to quantify antigenic differences, and (5) antigenic cartography to visualize relationships between strains [11]. These methods allow researchers to track gradual antigenic changes and select appropriate vaccine strains.

Recent advances in antigenic drift research include high-throughput pseudovirus neutralization assays and computational models predicting drift variants. For the H3N2 subclade K variant, researchers used ferret antisera raised against reference strains to measure antigenic distance through HI assays, demonstrating significant reduction in cross-reactivity compared to vaccine strains [11]. This serological validation is crucial for confirming that genetic changes correspond to meaningful antigenic differences. Additionally, machine learning approaches now incorporate both viral genomic data and population immunity profiles to forecast which drifted variants are likely to dominate future seasons, improving vaccine strain selection accuracy.

Diagram 1: Antigenic drift process showing how mutations accumulate under immune pressure.

Mapping Epistasis: Fitness Landscapes and Deep Mutational Scanning

Epistasis research employs combinatorial genetics and high-throughput fitness assays to quantify how genetic interactions shape evolutionary outcomes. The experimental protocol for constructing fitness landscapes involves: (1) selecting a set of mutations, (2) generating all possible combinations, (3) measuring fitness in relevant environments, and (4) modeling additive and epistatic effects [8]. For example, a hierarchical CRISPR gene drive system was used in budding yeast to construct all combinations of 10 missense mutations across the genome, creating a near-complete fitness landscape of 1024 genotypes [8]. This approach enabled researchers to quantify both pairwise and higher-order genetic interactions.

Deep mutational scanning (DMS) represents another powerful approach for studying epistasis, particularly in viral systems. DMS involves creating comprehensive mutant libraries and using deep sequencing to quantify variant frequencies before and after selection. The CoVFit model development utilized DMS data from 173,384 mutation-antibody combinations to understand how mutations affect neutralization escape [13]. This massive dataset allowed researchers to quantify epistatic interactions between mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and predict variant fitness. The statistical analysis of epistasis typically uses regularized regression models (like LASSO) to distinguish true genetic interactions from measurement noise and identify significant epistatic coefficients [8].

Diagram 2: Epistasis diagram showing how mutation effects depend on genetic background.

Protein Language Models: A Unified Approach

Protein language models represent a cutting-edge methodology that bridges the study of antigenic drift and epistasis. These models, adapted from natural language processing, learn evolutionary constraints from thousands of protein sequences and can predict the effects of mutations, including their epistatic interactions [13]. The CoVFit model development protocol involved: (1) domain adaptation of ESM-2 on coronavirus spike proteins, (2) multitask fine-tuning on genotype-fitness data from GISAID and DMS data from neutralization assays, (3) cross-validation to assess prediction accuracy [13]. This approach achieved remarkable performance (Spearman's correlation: 0.990) in ranking variant fitness, demonstrating the power of AI-based methods to capture complex evolutionary patterns.

The advantage of protein language models lies in their ability to handle never-before-seen mutations and capture higher-order epistatic effects without explicit training on every possible combination. Unlike traditional statistical models that treat fitness as a linear combination of mutation effects, language models learn the context-dependent effects of amino acid changes, naturally incorporating epistasis [13]. For drug development applications, these models can forecast which mutation combinations are likely to emerge in response to selective pressure, enabling proactive design of therapeutics and vaccines targeting future variants rather than past ones.

Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evolutionary Landscape Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial CRISPR Libraries | Generate complete genotype sets | Fitness landscape construction in yeast [8] |

| Protein Language Models (ESM-2) | Predict mutation effects from sequence | CoVFit model for SARS-CoV-2 fitness prediction [13] |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) | High-throughput mutation effect quantification | Mapping antibody escape mutations [13] |

| Monoclonal Antibody Panels | Probe antigenic regions and neutralization | Evaluating immune evasion potential [14] |

| Pseudovirus Neutralization Assays | Measure antibody escape without BSL-3 | Antigenic characterization of variants [11] |

| Barcode Sequencing Systems | Track genotype frequencies in pools | Competitive fitness measurements [8] |

The comparative analysis of antigenic drift and epistasis reveals distinct but complementary evolutionary forces shaping viral adaptation. While antigenic drift follows more predictable gradual patterns of change, epistasis creates complex, context-dependent evolutionary landscapes that challenge prediction efforts. The emerging research synthesis indicates that despite the idiosyncratic nature of individual genetic interactions, global statistical patterns emerge that can inform forecasting models [7] [8]. This understanding is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to anticipate viral evolution and design durable countermeasures.

Future directions in viral evolution research will likely focus on integrating multiple evolutionary concepts into unified predictive frameworks. Protein language models like CoVFit demonstrate how AI approaches can synthesize information from fitness landscapes, deep mutational scanning, and genomic surveillance to forecast variant emergence [13]. For drug development, this integration enables identifying mutation-resistant therapeutic targets and designing combination therapies that account for likely evolutionary escape pathways. Similarly, vaccine development can leverage these insights to target conserved epitopes with limited evolutionary capacity or design multivalent approaches covering likely drift trajectories. As these methods mature, the scientific community moves closer to proactive rather than reactive management of viral evolution.

The persistent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 has created a complex landscape of variants with altered phenotypic properties, presenting significant challenges to public health and therapeutic development. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that link specific mutations to changes in viral transmissibility and immune evasion remains a critical research objective. This guide systematically compares how key mutations in viral proteins, particularly the spike protein, translate into measurable phenotypic changes, framing these findings within the broader thesis of validating evolutionary predictions in viral research. By synthesizing experimental data from biochemical assays, viral fitness studies, and neutralization tests, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a structured analysis of mutation-driven viral adaptation, highlighting the experimental frameworks that enable precise mapping from genetic sequence to functional outcome.

Comparative Phenotypic Profiles of Key SARS-CoV-2 Mutations

Structural and Functional Impacts of Spike Protein Mutations

Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein represent a primary mechanism for viral adaptation, directly influencing receptor binding, structural stability, and antibody recognition. Integrated molecular dynamics analyses reveal that viral adaptation hinges on evolutionary trade-offs between transmissibility and immune escape [15]. The following table summarizes the biophysical and phenotypic impacts of key characterized mutations:

Table 1: Biophysical and Phenotypic Impacts of Characterized Spike Mutations

| Mutation | Location | Biophysical Impact | Functional Consequence | Variant Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T478K | RBD | Enhances ACE2 binding through structural rigidification and salt bridge formation (e.g., K478-D30) [15] | Increased transmissibility [15] | Delta, Omicron [15] |

| E484K | RBD | Disrupts antibody-binding sites (e.g., for LY-CoV555); introduces compensatory interactions (e.g., K484-D38) for receptor stabilization [15] | Significant immune evasion; reduced neutralization by vaccines and monoclonal antibodies [15] | Beta, Gamma [15] |

| L455S | RBD | Distant from furin cleavage site but reduces spike cleavage efficiency [16] | Enhanced immune evasion; moderate reduction in replication [16] | JN.1 [16] |

| F456L | RBD | Part of the "FLip" and "FLiRT" mutation constellations [16] | Contributes to immune evasion; often co-occurs with other RBD mutations [16] | JN.1 descendants (KP.2, KP.3) [16] |

| Q493E | RBD | Can influence spike cleavage despite distance from cleavage site [16] | Enhances viral replication fitness [16] | KP.3 [16] |

| Y369C | NTD | Collapses the N-terminal domain supersite [15] | Significant immune evasion; requires compensatory mutations (e.g., G142D) for viability [15] | Emerging variants [15] |

Replication Fitness and Immune Evasion in BA.2.86 Descendants

The evolutionary progression from BA.2.86 to its descendants (JN.1 → KP.2 → KP.3) demonstrates how sequential mutations fine-tune viral properties through constellations of mutations that collectively optimize fitness. Comparative analysis using recombinant SARS-CoV-2 strains in primary human airway epithelium (HAE) cells reveals how specific mutations drive epidemiological succession:

Table 2: Evolutionary Progression and Properties of BA.2.86 Lineage

| Variant | Key Spike Mutations | Replication Fitness in HAE Cells | Immune Evasion Capability | Epidemiological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA.2.86 | Baseline (>30 spike mutations compared to BA.2) [16] | Baseline | Baseline | Parental lineage for subsequent descendants [16] |

| JN.1 | L455S (additional) [16] | Reduced compared to BA.2.86 [16] | More resistant to XBB.1.5-infection sera than BA.2.86 [16] | Primary driver: immune evasion [16] |

| KP.2 | R346T, L455S, F456L ("FLiRT") [16] | Enhanced replication compared to JN.1 [16] | Increased resistance to JN.1-infection sera [16] | Combined immune evasion and fitness advantage [16] |

| KP.3 | L455S, F456L, Q493E [16] | Greater replication than KP.2 [16] | Similar neutralization sensitivity to JN.1-infection sera [16] | Primary driver: enhanced replication fitness [16] |

Non-Spike Driver Mutations in Viral Evolution

Beyond the spike protein, mutations in non-structural proteins can significantly influence evolutionary trajectories. The NSP4 T492I mutation functions as an evolutionary driver that predisposes viruses toward Omicron-like evolution [17]. Experimental evolve-and-resequence studies demonstrate that SARS-CoV-2 populations containing T492I consistently evolved enhanced replication capacity, infectivity, and immune evasion compared to controls [17]. This mutation demonstrates how non-structural proteins can influence global evolutionary landscapes through positive epistasis with adaptive mutations in other viral proteins and by elevating mutation rates, potentially through alterations in RNA-editing enzyme expression [17].

Experimental Frameworks for Mutation-to-Phenotype Mapping

Key Experimental Protocols

Evolve-and-Resequence Experiments

- Objective: To experimentally evaluate how specific mutations influence long-term viral evolution [17]

- Protocol: Serial passaging of replicate SARS-CoV-2 populations (wild-type and isogenic T492I mutants) on Calu-3 human lung epithelial cells over 90 days (30 transmission events) with parallel independent replicates [17]

- Measurements: Periodic sequencing to track mutation accumulation; comparison of evolved populations for replication kinetics (viral RNA quantification by RT-qPCR), infectivity (plaque assay), and immune evasion (serum neutralization assays) [17]

- Applications: Identification of driver mutations that accelerate adaptive evolution; analysis of mutation-driven predisposition to specific variant lineages [17]

Pairwise Competition Assays for Viral Fitness

- Objective: To precisely compare replication fitness between closely related variants [16]

- Protocol: Co-infect primary human airway epithelium (HAE) cells with two recombinant SARS-CoV-2 strains, each engineered with distinct fluorescent markers (e.g., mNeonGreen variants); track relative proportion over multiple replication cycles using flow cytometry or sequencing [16]

- Measurements: Fitness differences calculated from changes in variant ratios over time; neutralization sensitivity assessed using fluorescent focus reduction neutralization test (FFRNT) with human convalescent sera [16]

- Applications: Quantitative comparison of viral fitness independent of differential immune recognition; identification of subtle fitness advantages conferred by specific mutations [16]

Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Mutational Impacts

- Objective: To predict biophysical consequences of mutations on protein structure and interaction dynamics [15]

- Protocol: Introduce mutations into crystal structures of spike protein (PDB ID: 6M0J) and ACE2 receptor (PDB ID: 1R42) using molecular modeling software (e.g., PyMOL); run all-atom molecular dynamics simulations to analyze structural rigidification, binding affinity changes, and electrostatic interactions [15]

- Measurements: Binding free energy calculations (MM/GBSA); salt bridge formation and stability; conformational flexibility; receptor-binding domain dynamics [15]

- Applications: Mechanistic understanding of how mutations alter ACE2 binding affinity or antibody escape; prediction of functional impacts prior to experimental testing [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Viral Evolution and Characterization Studies

| Reagent / System | Function / Application | Experimental Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Airway Epithelium (HAE) Cells | Physiologically relevant ex vivo model of human respiratory infection [16] | Measurement of viral replication kinetics in authentic human respiratory tissue; competition assays between variants [16] |

| Vero E6-TMPRSS2 Cells | Monkey kidney epithelial cells engineered to express human TMPRSS2 protease [16] | Efficient propagation of clinical virus isolates; recovery of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 from infectious clones [16] |

| Recombinant mNeonGreen SARS-CoV-2 | Fluorescent reporter viruses for live-cell imaging and rapid quantification [16] | High-throughput neutralization assays (FFRNT); real-time tracking of viral spread in cell culture [16] |

| Human Convalescent Sera Panels | Source of polyclonal antibody responses from recovered or vaccinated individuals [16] | Assessment of immune evasion by new variants; measurement of neutralization titers against emerging variants [16] |

| Phosphorylethanolamine-d4 | Phosphorylethanolamine-d4 Stable Isotope|1169692-38-9 | |

| H-Gly-Pro-Gly-NH2 | H-Gly-Pro-Gly-NH2, CAS:141497-12-3, MF:C9H16N4O3, MW:228.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Experimental and Evolutionary Relationships

Mutation to Phenotype Mapping Pathways

Experimental Evolution Workflow

Validation of Evolutionary Predictions in Viral Research

The experimental characterization of mutation-to-phenotype relationships provides critical validation for computational frameworks predicting viral evolution. The EVEscape platform exemplifies this approach, combining deep learning models trained on pre-pandemic coronavirus sequences with biophysical and structural information to successfully forecast SARS-CoV-2 immune escape mutations before they reached high frequency in the population [18]. This demonstrates that preparedness strategies can leverage evolutionary predictions to anticipate variant emergence. Furthermore, theoretical models incorporating trade-offs between immune evasion and transmissibility accurately describe observed evolutionary patterns, where highly transmissible strains tend to evolve toward immune evasion, while less transmissible strains evolve toward increased transmissibility [1]. The experimental confirmation of these predictions, particularly through evolve-and-resequence studies that recapitulate evolutionary trajectories [17], strengthens our fundamental understanding of viral adaptation and provides a validated framework for forecasting future variant emergence.

Predicting viral evolution represents a monumental challenge and a critical objective in modern public health. The ability to forecast how pathogens will evolve to evade immune responses would transform pandemic preparedness, shifting the response strategy from being reactive to proactive. Historically, strategies to address viral evolution have relied on responding to emerging variants after their detection, leading to inevitable delays in effective public health interventions [19]. However, the synergistic convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) with the massive-scale viral data collection infrastructures developed during the COVID-19 pandemic has created a research ecosystem highly conducive to achieving this long-standing goal [19]. This guide objectively compares the emerging computational and experimental frameworks designed to anticipate viral evolution, validating their performance through quantitative metrics and experimental data. For researchers and drug development professionals, the validation of these predictive models is not merely an academic exercise but a crucial step towards developing durable vaccines and therapeutics that can stay ahead of the evolutionary curve.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Frameworks

The following section provides a structured comparison of the dominant approaches for forecasting viral evolution, focusing on their underlying methodologies, data requirements, and output capabilities.

Framework Comparison Table

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of three primary prediction approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Viral Evolution Prediction Frameworks

| Feature | EVEscape Framework | Traditional Surveillance-Based Models | High-Throughput Experimental Scans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Deep learning (variational autoencoder) combined with biophysical/structural constraints [18] | Phylogenetic analysis & current strain prevalence [18] | Pseudovirus assays & deep mutational scans (DMS) [18] |

| Primary Data Input | Historical viral protein sequences (pre-pandemic), 3D structures [18] | Recent pandemic surveillance sequences (e.g., GISAID) [18] | Polyclonal antibodies/sera, mutant libraries [18] |

| Key Output | Standardized escape score quantifying immune evasion potential [18] | Identification of currently circulating variants of concern | Experimental measurements of antibody binding for thousands of variants [18] |

| Lead Time | High (applicable before pandemic onset) [18] | Low (reacts to already-circulating strains) | Medium (requires representative antibodies post-infection/vaccination) [18] |

| Epistasis Handling | Captures dependencies across positions via deep generative model [18] | Limited, often assumes additive effects | Can test specific combinations but is resource-intensive |

| Throughput | Extremely high (can assess all possible mutations at scale) [18] | High for monitoring, limited for prediction | High, but testing all variants is intractable [18] |

Performance Benchmarking

Quantitative validation is essential for establishing the reliability of any predictive framework. The performance of the EVEscape framework was rigorously tested in a retrospective study simulating a pre-pandemic scenario.

Table 2: Performance Benchmark of EVEscape Against Experimental and Observational Data

| Validation Metric | Virus Tested | EVEscape Performance | Benchmark/Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antigenic Region Identification | SARS-CoV-2 (Spike) | Top predictions strongly biased towards RBD & NTD [18] | Coincident with known antigenic regions [18] |

| Correlation with Fitness Experiments | Influenza | Spearman Ï = 0.53 with viral replication data [18] | Approaches replicate correlation (Ï = 0.53) [18] |

| Correlation with Fitness Experiments | HIV | Spearman Ï = 0.48 with viral replication data [18] | Approaches replicate correlation (Ï = 0.48) [18] |

| Pandemic Mutation Forecasting | SARS-CoV-2 (RBD) | 50% of top predictions observed by May 2023 [18] | 66% of high-frequency mutations were top predictions [18] |

| Comparison to Experimental Scans | SARS-CoV-2 | As accurate as high-throughput experimental scans [18] | Provides comparable prioritization without requiring antibodies [18] |

The data demonstrates that EVEscape can identify immunogenic domains like the Receptor-Binding Motif without prior knowledge of specific antibodies, which is crucial for early subunit vaccine design [18]. Furthermore, its performance in predicting mutations that later appeared at high frequency in the pandemic underscores its utility in forecasting variants of concern.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

A critical step in trusting any predictive model is independent validation. The following protocols outline the key methodologies used to generate the benchmark data.

Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS)

Purpose: To experimentally measure the functional effect of thousands of single amino acid mutations on viral protein properties such as receptor binding, expression, and antibody escape [18].

Workflow:

- Library Construction: Create a vast library of viral gene variants (e.g., for the SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD) where each variant contains a single point mutation.

- Selection Pressure: Subject the variant library to a relevant selection pressure, such as incubation with host receptor protein (e.g., ACE2) or a panel of neutralizing antibodies.

- Sequencing and Enrichment Analysis: Use deep sequencing to quantify the frequency of each variant before and after selection. Mutations that are enriched after selection for receptor binding are considered fitness-enhancing, while those enriched after antibody pressure are potential escape mutations.

- Data Normalization: Calculate enrichment scores for each mutation, which represent its functional effect under the given condition.

Retrospective Predictive Validation

Purpose: To assess a model's performance by training it exclusively on data available before a specific date and testing its predictions against future observational data [18].

Workflow:

- Time-Stamped Training: Train the predictive model (e.g., EVEscape) using only viral sequence data and structural information available before the emergence of the target virus (e.g., using coronavirus sequences available before January 2020).

- Generate Predictions: Run the model to generate a ranked list of high-priority escape mutations for the viral antigen.

- Compare with Observational Data: Compare the model's predictions against the mutations that subsequently emerged and were documented in global surveillance databases like GISAID over a defined period (e.g., until May 2023).

- Quantitative Metrics: Calculate performance metrics, such as the percentage of top-ranked predictions that were observed and the enrichment of high-frequency mutations among the top predictions.

Conceptual Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical relationships and workflows of the key concepts and frameworks discussed.

Viral Escape Prediction Concept

EVEscape Framework Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Translating predictive models into tangible public health tools requires a suite of specialized reagents and resources. The following table details key materials essential for work in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Evolution Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Primary Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudovirus Libraries | Safe, replication-incompetent viruses engineered to express variant viral proteins (e.g., Spike) on their surface [18]. | High-throughput measurement of how mutations affect antibody neutralization and receptor usage [18]. |

| Polyclonal Antibody Sera | Complex mixture of antibodies from convalescent or vaccinated individuals, representing the aggregate immune pressure [18]. | Used as selection pressure in DMS or neutralization assays to identify mutations that confer broad escape from human immune responses. |

| Reference Antigenic Panels | Curated sets of viral strains or recombinant proteins representing historical and current circulating variants. | Standardized assessment of antigenic drift and the cross-reactivity of vaccines/therapeutics against diverse strains. |

| Global Sequence Databases (GISAID) | International repository of genetic sequence data from influenza and coronavirus pathogens [18]. | Serves as the ground-truth dataset for retrospective validation of predictive models and for tracking the real-world emergence of variants. |

| Structural Models (PDB) | Experimentally determined (e.g., Cryo-EM) 3D structures of viral proteins and protein-antibody complexes. | Informs the biophysical constraints in models like EVEscape, allowing for computation of residue accessibility and interpretation of escape mechanisms [18]. |

| Norneostigmine | Norneostigmine, CAS:16088-19-0, MF:C11H16N2O2, MW:208.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mergetpa | Mergetpa (Plummer's Inhibitor) |

The critical public health need for predicting viral evolution is unequivocal. As the comparative analysis shows, frameworks like EVEscape, which leverage deep learning on historical data and biophysical principles, offer a powerful and generalizable approach for early warning that complements traditional surveillance and high-throughput experiments [18]. However, meaningful prediction is not solely a computational or genetic challenge; it requires a profound synthesis of genetic insights with ecological and epidemiological perspectives [20]. Factors such as host population density, animal biodiversity, and human disturbance are fundamental drivers of cross-species transmission and emergence events [20]. The future of outbreak response lies in integrating these diverse data streams—genomic, structural, ecological, and immunological—into a unified forecasting system. For researchers and drug developers, this integrated approach provides a more robust foundation for designing broadly effective "variant-proof" countermeasures, ultimately enabling a more resilient global defense against the perpetual threat of viral evolution.

A Toolkit for Prediction: Integrative Models, AI, and Machine Learning

In viral evolution research, fitness represents a variant's relative effective reproduction number (Râ‚‘), determining its competitive success in a host population with specific immunity landscapes [13]. Integrative fitness models represent a transformative approach by moving beyond single-data-type analyses to combine genetic, antigenic, and epidemiological information. These models aim to predict viral evolution by quantifying how mutations influence phenotypic properties like transmissibility and immune escape, which collectively determine a variant's overall fitness [2] [13].

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that successive SARS-CoV-2 variants drove repeated epidemic surges through escalated fitness, with early variants (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta) largely driven by increased intrinsic transmissibility, while later Omicron-derived lineages (XBB, EG.5.1, JN.1) were primarily driven by immune escape [2]. This transition from transmissibility-driven to immune escape-driven success emerges directly from the interplay between population immunity and variant fitness, creating a complex evolutionary landscape that only integrative models can adequately capture [2].

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Integrative Fitness Modeling Platforms

| Model Name | Primary Data Inputs | Methodological Approach | Key Outputs | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoVFit [13] | Spike protein sequences; Genotype-fitness data; Deep mutational scanning (DMS) data | Protein language model (ESM-2 adaptation); Multitask learning framework | Variant fitness predictions; Immune escape potential | Spearman's correlation: 0.990 for fitness ranking; 0.578-0.814 for escape prediction |

| Gaussian Process Framework [2] | Variant frequency time series; Genetic data | Hilbert Space Gaussian Process (HSGP) approximation; Non-parametric fitness estimation | Time-varying relative fitness; Selective pressure metrics | Early signal of epidemic growth using genetic data alone |

| Mechanistic Compartmental Models [2] | Serological data; Vaccination history; Variant frequencies | Compartmental models of infectious diseases; Cross-immunity structures | Relative fitness dynamics; Transmission parameters | Explains geographic and temporal heterogeneity in variant advantages |

| Tris(2,4-DI-tert-butylphenyl)phosphate | Tris(2,4-DI-tert-butylphenyl)phosphate, CAS:95906-11-9, MF:C42H63O4P, MW:662.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Silibinin B | Silybin B - CAS 142797-34-0 - For Research Use | Silybin B (Silibinin B), a flavonolignan from milk thistle. Key applications include oncology and neurobiology research. This product is for research use only (RUO), not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Characteristics and Applications of Modeling Approaches

| Model Characteristic | CoVFit | Gaussian Process Framework | Mechanistic Compartmental Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction Timeliness | Immediate upon sequence availability (single sequence sufficient) | Requires accumulation of variant frequency data | Requires multiple data types including serology |

| Mechanistic Insight | High (connects genotypes to functional consequences) | Medium (infers patterns without explicit mechanisms) | High (explicit transmission mechanisms) |

| Epistasis Handling | High (protein language models capture context-dependent mutation effects) | Limited (primarily statistical patterns) | Variable (depends on model structure) |

| Data Requirements | Sequence data + existing fitness/escape datasets | Temporal variant frequency data | Multiple data streams (serology, transmission, sequences) |

| Primary Application | Flagging high-risk variants; Exploring fitness landscapes | Real-time fitness estimation; Forecasting variant growth | Understanding transmission dynamics; Public health planning |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protein Language Model Development (CoVFit Protocol)

The CoVFit model exemplifies the integrative approach through its sophisticated training methodology [13]:

Domain Adaptation Phase:

- Base ESM-2 model undergoes additional pretraining on spike protein sequences from 1,506 Coronaviridae viruses

- Creates ESM-2Coronaviridae with enhanced predictive capability for SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins

- Validation through masked learning tasks demonstrates improved performance

Multitask Learning Framework:

- Model fine-tuning simultaneously utilizes two data types:

- Genotype-fitness data (21,281 data points covering 12,817 genotypes across 17 countries)

- Deep mutational scanning data (173,384 mutation-monoclonal antibody measurements)

- Fitness data derived from GISAID sequences up to November 2023 using multinomial logistic models

- DMS data covers 2,096 RBD mutations and 1,548 mAbs from Cao et al.

Cross-Validation Strategy:

- Five-fold cross-validation scheme generates five model instances

- Provides mean and variance estimates for predictions on new variants

- Primary evaluation metric: Spearman's rank correlation for fitness ranking prediction

Figure 1: CoVFit protein language model development and training workflow

Time-Varying Fitness Estimation Protocol

The Gaussian Process framework addresses the critical challenge of non-constant relative fitness [2]:

Data Preparation:

- Collect variant frequency time series from genomic surveillance

- Calculate prevalence measures for each variant over time

- Organize data by geographic regions to account for immune heterogeneity

Model Specification:

- Implement Hilbert Space Gaussian Process (HSGP) approximation for computational scalability

- Define kernel structure encoding temporal correlations and smoothness constraints

- Model relative fitness as: λᵥ,ᵤ(t) = rᵥ(t) - rᵤ(t), where r represents variant growth rates

Estimation Procedure:

- Infer posterior distributions of time-varying fitness parameters

- Calculate selective pressure metric from fitness dynamics

- Validate using simulated data with known fitness parameters

Mechanistic Model Integration Protocol

Integrative models connecting frequency dynamics to transmission mechanisms involve [2]:

Immune Landscape Characterization:

- Estimate population susceptibility profiles from vaccination and infection history

- Parameterize cross-immunity structures using serological data or deep mutational scanning

- Define immune backgrounds (pseudo-immune groups) affecting variant transmission

Variant-Specific Parameterization:

- Estimate intrinsic transmissibility coefficients (Ï) for each variant

- Quantify immune escape proportions (η) against existing immunity

- Calculate critical immune fraction Ï•* = Ï/(η+Ï) determining fitness trade-offs

Dynamic Fitness Calculation:

- Compute relative fitness as weighted combinations of immune background functions

- Project short-term fitness changes using Taylor expansion approximations

- Validate predictions against observed variant frequency trajectories

Signaling Pathways and Theoretical Frameworks

Variant Fitness Determination Pathway

Variant fitness emerges from complex interactions between viral properties and population immunity, represented through several interconnected pathways [2] [13].

Figure 2: Pathways determining viral variant fitness from genotype to population dynamics

The framework shows how genotype influences phenotypic properties (transmissibility and immune escape), which interact with population immunity to determine relative fitness. This fitness ultimately drives variant replacement patterns observed in surveillance data [2]. The critical insight is that the same mutation can have different fitness effects depending on the immune background it encounters, explaining why variant advantages differ geographically and temporally [2].

Antigen Archiving and Immune Memory Pathway

Beyond immediate fitness considerations, antigen archiving in lymph nodes represents a crucial mechanism influencing long-term immune responses and viral evolution trajectories [21].

Figure 3: Antigen archiving pathway in lymph nodes and role in immune memory

Lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), particularly ceiling and floor LECs in the subcapsular sinus, actively acquire and archive foreign antigens for extended periods (up to 42 days in studied models) [21]. This archiving process follows a specific transcriptional program that predicts archiving capacity across different disease states and organisms. Archived antigens can be transferred to migratory dendritic cells (CCR7Ê°â± migratory cDCs), which subsequently promote memory T cell responses, creating a bridge between innate antigen capture and adaptive immune memory [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Integrative Fitness Modeling

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 Model [13] | Protein Language Model | Base architecture for understanding sequence-function relationships | Adapted to create CoVFit for fitness prediction |

| GISAID Database [13] | Genomic Data Repository | Source for variant sequences and temporal frequency data | Genotype-fitness relationship derivation; Surveillance data |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) Data [13] | Experimental Dataset | High-throughput measurement of mutation effects on antibody escape | Informs fitness models about immune evasion potential |

| Ovalbumin-psDNA Conjugate [21] | Antigen Tracking Tool | DNA-barcoded antigen for quantifying acquisition and retention | Studying antigen archiving dynamics in lymph nodes |

| Hilbert Space Gaussian Process (HSGP) [2] | Computational Method | Scalable approximation for Gaussian process regression | Enables time-varying fitness estimation from frequency data |

| scRNA-seq with Antigen Detection [21] | Analytical Platform | Single-cell resolution of cell phenotypes plus antigen levels | Identifying antigen-archiving cell populations and programs |

Integrative fitness models represent the cutting edge in viral evolution forecasting, combining diverse data types to overcome limitations of single-approach methodologies. The comparative analysis demonstrates that protein language models like CoVFit excel at predicting variant fitness from sequence data alone, while Gaussian process approaches better capture time-varying fitness dynamics, and mechanistic models provide deeper insights into the underlying transmission biology [2] [13].

These approaches collectively advance the fundamental goal of predicting viral evolution before variants reach substantial frequencies, potentially enabling proactive public health responses. As these models continue to develop and incorporate additional data dimensions—including detailed antigen archiving dynamics [21] and advanced protein language representations [13]—they promise to transform our ability to anticipate and manage viral infectious disease threats. The validation of evolutionary predictions through these integrative frameworks represents a crucial step toward proactive pandemic preparedness and optimized countermeasure development.

In the ongoing battle against viral pandemics, a fundamental shift is occurring: from reactive responses to proactive forecasting of viral evolution. The rapid mutation of viruses like SARS-CoV-2, which continually morphs to slip past vaccines and therapies, underscores the critical need for predictive tools that can anticipate viral variants before they become widespread [22]. The emerging field of AI-powered viral forecasting aims to address this challenge by leveraging artificial intelligence to interpret evolutionary and biological data, potentially enabling researchers to design vaccines and therapeutics that remain effective against future variants [23]. This comparison guide examines leading computational frameworks—EVEscape, HELEN, CoVFit, and SVEP—evaluating their methodologies, performance, and applicability for researchers and drug development professionals working to validate evolutionary predictions in viral evolution research.

Each tool represents a distinct approach to a common problem: how to accurately predict which viral mutations will prevail, considering both the constraints of viral fitness and the selective pressure from population immunity. EVEscape combines deep generative models with structural biology, while HELEN focuses on epistatic networks and community detection [18] [24]. CoVFit employs protein language models specifically tuned for fitness prediction, and SVEP introduces a linguistic framework analyzing "grammatical" rules in viral sequences [5] [25]. Understanding their comparative strengths and experimental validations provides crucial insights for scientists selecting appropriate tools for pandemic preparedness and therapeutic development.

Comparative Framework Analysis

EVEscape: A Modular Framework for Forecasting Viral Escape

EVEscape operates on a foundational premise: viral antibody escape mutations must achieve two objectives—disrupt antibody binding while maintaining viral fitness [18]. This modular framework strategically integrates multiple data sources to quantify this escape potential. Its fitness component utilizes EVE (evolutionary model of variant effect), a deep generative model trained on vast datasets of evolutionarily related protein sequences that capture complex epistatic constraints essential for predicting viable mutations [18] [22]. The framework incorporates an accessibility term derived from structural information, quantifying how exposed residues are to antibody binding based on their protrusion from the protein core and conformational flexibility [18]. Finally, a dissimilarity term estimates the potential for mutations to disrupt antibody binding through changes in key biophysical properties like hydrophobicity and charge [18].

A key innovation of EVEscape is its minimal dependency on pandemic-era data. In a compelling retrospective analysis, researchers demonstrated that EVEscape, trained exclusively on pre-pandemic coronavirus sequences available before January 2020, successfully identified SARS-CoV-2 mutations that subsequently emerged as significant during the pandemic [18]. The tool achieved accuracy comparable to high-throughput experimental scans in predicting viral variation, with 50% of its top-ranked RBD predictions being observed in the pandemic by May 2023, rising to 66% for high-frequency substitutions [18]. This performance demonstrates that evolutionary history combined with structural information can effectively forecast future viral evolution, providing a crucial early-warning capability for emerging pathogens.

HELEN: Early Detection Through Coordinated Substitution Networks

In contrast to EVEscape's approach, the HELEN (Heralding Emerging Lineages in Epistatic Networks) framework addresses the critical challenge of epistasis—non-additive interactions between mutations that significantly influence viral fitness and evolution [24]. HELEN operates on the principle that selection acts on combinations of mutations (haplotypes) rather than individual mutations, and that these emerging haplotypes can be detected through analysis of coordinated substitution networks before they become prevalent [24].

HELEN's methodology involves constructing networks where nodes represent specific mutations, and edges represent statistical associations between these mutations across viral sequences. Dense communities within these networks signal potentially beneficial combinations of mutations that are co-evolving. This network-based approach allows HELEN to identify viral variants significantly earlier than traditional phylogenetic methods—in some cases, months before World Health Organization designations—by detecting these coordinated mutation patterns when they first begin to emerge in the viral population [24]. A significant advantage of this method is its computational efficiency, as its complexity depends on genome length rather than the number of sequences, enabling it to scale effectively to analyze millions of available SARS-CoV-2 genomes [24].

CoVFit: Language Models for Fitness Prediction

CoVFit represents another distinct methodological approach, leveraging protein language models specifically adapted to predict viral fitness based on spike protein sequences alone [5]. Built upon ESM-2, a state-of-the-art protein language model, CoVFit undergoes a two-stage adaptation process: first through additional pre-training on Coronaviridae spike protein sequences (creating ESM-2Coronaviridae), followed by multi-task fine-tuning using both genotype-fitness data derived from viral surveillance and deep mutational scanning data measuring antibody escape potential [5].

This dual training enables CoVFit to predict variant fitness (defined as relative effective reproduction number) from spike protein sequences, successfully ranking the fitness of future variants containing nearly 15 mutations with informative accuracy [5]. The model identified 959 fitness elevation events throughout SARS-CoV-2 evolution until late 2023, demonstrating its utility in tracking viral adaptation. Unlike methods that require structural information or experimental data, CoVFit's language model-based approach can make predictions based solely on sequence information, offering potential applications for viruses with limited characterization [5].

SVEP: A Linguistic Framework for Mutation Prediction

The Semantic Model for Variants Evolution Prediction (SVEP) introduces a distinctive linguistic analogy, treating viral proteins as following "grammatical" rules that constrain their evolutionary possibilities [25]. SVEP's methodology involves constructing "grammatical frameworks" from viral sequences by identifying conserved and variable regions ("hot spots"), then grouping related positions into hierarchical "word," "sentence," and "paragraph" clusters that capture long-range interactions within the protein [25].

This framework incorporates both evolutionary constraints ("regularity") and mutation randomness. The model employs Monte Carlo simulations constrained by observed amino acid collocation patterns to generate potential future sequences, while introducing a "mutational profile" variable to incorporate random mutation events [25]. This combination allows SVEP to generate predictions that respect biological constraints while exploring novel mutations. Researchers validated SVEP by successfully detecting circulating strains and key mutations for variants like XBB.1.16, EG.5, and JN.1 before their emergence, demonstrating forecasting capability with lead time for vaccine development [25].

Performance Comparison & Experimental Validation

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of AI Forecasting Tools

| Tool | Primary Prediction Target | Key Performance Metrics | SARS-CoV-2 Validation Results | Generalizability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVEscape | Antibody escape potential | Ranking accuracy of escape mutations | 50% of top RBD predictions observed by May 2023; 66% of high-frequency mutations predicted [18] | Validated on HIV, influenza, Lassa, Nipah [18] [22] |

| HELEN | Emerging haplotypes/variants | Early detection time before designation | Identification of known VOCs/VOIs months before WHO designation [24] | Methodologically generalizable to any rapidly evolving pathogen [24] |

| CoVFit | Variant fitness (relative Re) | Spearman's correlation for fitness ranking | Successively ranked fitness of future variants (~15 mutations) with high accuracy [5] | Architecture adaptable to other viruses via retraining [5] |

| SVEP | Emerging variants and mutations | Lead time for variant detection | Detected key mutations for XBB.1.16, EG.5, JN.1 before emergence [25] | Framework applicable to other viral pathogens [25] |

Methodological Comparison

Table 2: Methodological Approaches and Data Requirements

| Tool | Core Methodology | Key Data Inputs | Epistasis Handling | Implementation Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVEscape | Deep generative model (EVE) + structural/biophysical constraints | Evolutionary sequences, protein structures | Captured through deep learning on sequence ensembles [18] | GitHub repository (OATML-Markslab/EVEscape) [26] |

| HELEN | Coordinated substitution network analysis | Viral genome sequences | Core focus through detection of mutation co-occurrence [24] | Not specified in available sources |

| CoVFit | Protein language model (ESM-2) fine-tuning | Spike protein sequences, fitness estimates, DMS data | Implicitly captured through language model embeddings [5] | Not specified in available sources |

| SVEP | Linguistic framework with Monte Carlo simulation | Viral protein sequences | Captured through "grammatical" collocation patterns [25] | Not specified in available sources |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

EVEscape's Validation Protocol

EVEscape's validation involved a rigorous retrospective analysis designed to simulate real-world forecasting conditions. Researchers trained the model exclusively on pre-pandemic data—coronavirus sequences available before January 2020—then evaluated its predictions against SARS-CoV-2 mutations that actually emerged during the pandemic [18]. This temporal separation between training and evaluation data provided a robust test of genuine predictive capability rather than mere data fitting.

The experimental validation compared EVEscape predictions against several benchmarks: (1) actual mutations observed in GISAID sequences (over 750,000 unique SARS-CoV-2 sequences); (2) results from high-throughput experimental deep mutational scans measuring antibody escape; and (3) alternative computational methods [18]. Performance was quantified using ranking accuracy—the proportion of top-ranked predictions that subsequently emerged as actual mutations—stratified by mutation frequency. This approach demonstrated that EVEscape's predictions became increasingly accurate over time, with the proportion of predicted mutations observed rising from 3% in December 2020 to 50% by May 2023, reflecting increasing immune pressure on the virus [18].

HELEN's Early Detection Framework

HELEN's validation focused on its core claim: early detection of emerging variants before they reach significant prevalence. Researchers tested this capability using historical SARS-CoV-2 sequence data, applying HELEN to data from timepoints preceding the emergence of known Variants of Concern (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, Omicron) and Variants of Interest (Lambda, Mu, Theta, Eta, Kappa) [24].

The protocol involved constructing coordinated substitution networks from spike protein sequences, identifying dense communities within these networks, and then tracking whether these communities corresponded to emerging lineages. To ensure robustness, analyses were performed on three distinct datasets: a complete dataset, and two truncated datasets excluding sequences flagged as "under investigation" or early-sampled sequences not initially recognized as significant [24]. This multi-dataset approach confirmed that predictions were not artifacts of potentially mislabeled sequences. The study analyzed 656 test cases (16 countries × 41 timepoints), demonstrating HELEN's ability to identify variants months before conventional surveillance methods across diverse geographical contexts [24].

Methodological Workflows

EVEscape Workflow

EVEscape Modular Framework. The workflow integrates fitness predictions from deep learning models with structural and biophysical constraints to quantify viral escape potential [18].

HELEN Network Analysis Workflow

HELEN Network Detection. Workflow for constructing coordinated substitution networks and detecting emerging viral haplotypes through community detection [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Viral Forecasting Studies

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | GISAID [24], GenBank | Source of viral sequences for training and validation | Curated collections with metadata; GISAID specifically designed for global pathogen surveillance |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) | Pseudovirus assays [18], yeast-display [18] | High-throughput experimental validation of mutation effects | Enables testing of thousands of mutations for antibody binding, protein expression, receptor affinity |

| Structural Biology Resources | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold | Source of 3D protein structures for accessibility calculations | Enables residue-level analysis of antibody binding sites and conformational flexibility |

| Computational Frameworks | ESM-2 [5], EVE [18] | Pre-trained models for protein sequence analysis | Capture evolutionary constraints and epistatic interactions through deep learning |

| Experimental Validation Systems | HIV-1 pseudovirus assays [25], neutralization assays | Functional testing of predicted mutations | Provide wet-lab confirmation of computational predictions for immune escape and infectivity |

| Apixaban-d3 | Apixaban-d3|CAS 1131996-12-7|Internal Standard | Apixaban-d3 is a deuterated internal standard for precise UPLC-MS/MS quantification of apixaban in plasma. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Cinnamic Acid | Cinnamic Acid|High-Purity Research Compound Supplier | Research-grade Cinnamic Acid for investigating anticancer, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

The development of AI-powered forecasting tools represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach viral evolution, moving from reactive characterization to proactive prediction. Each framework examined offers distinct advantages: EVEscape's robust integration of evolutionary and structural constraints; HELEN's sensitivity to emerging haplotypes through network analysis; CoVFit's precise fitness predictions from sequence alone; and SVEP's innovative linguistic approach [18] [24] [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these tools provide complementary capabilities for addressing the fundamental challenge of viral evolution.

The consistent validation of these tools against historical SARS-CoV-2 data provides compelling evidence for their utility in pandemic preparedness. Their ability to accurately predict mutations that subsequently emerged demonstrates that viral evolution, while possessing stochastic elements, follows patterns detectable through sophisticated computational analysis [18] [25]. As these tools continue to develop and integrate additional data types—including real-time surveillance, immunological profiling, and detailed biophysical measurements—they offer the promise of genuinely proactive vaccine and therapeutic design, potentially creating interventions that remain effective against future viral variants. For the research community, these tools represent not just analytical methods but fundamental components of a new approach to managing viral threats—one based on anticipation rather than reaction.