Managing Life-History Evolution in Harvested Populations: From Theory to Adaptive Intervention

This article synthesizes the critical interplay between harvesting practices and the evolutionary trajectories of exploited populations.

Managing Life-History Evolution in Harvested Populations: From Theory to Adaptive Intervention

Abstract

This article synthesizes the critical interplay between harvesting practices and the evolutionary trajectories of exploited populations. It explores the foundational principles of life-history theory that predict how traits like age and size at maturation evolve under selective mortality. For researchers and applied scientists, we review methodological frameworks for detecting and modeling fisheries-induced evolution (FIE), analyze the demographic and genetic consequences such as reduced effective population size, and evaluate management and intervention strategies. By integrating theoretical predictions with empirical validation from long-term studies and models, this review provides a comprehensive resource for understanding and mitigating the evolutionary impacts of harvest to promote sustainable population management and resilience.

Life-History Theory and the Evolutionary Drivers of Harvest-Induced Change

Core Principles of Life-History Evolution and Trade-offs

Life-history theory is an analytical framework in evolutionary ecology that seeks to explain the remarkable diversity of life cycles and strategies observed among organisms [1] [2]. This theory studies how natural selection and other evolutionary forces shape organisms to optimize their survival and reproduction when faced with ecological challenges [2]. The central premise is that organisms face inherent trade-offs in allocating limited resources to competing life functions, leading to the evolution of characteristic life history strategies [1] [3].

In the context of managing harvested populations, understanding these trade-offs becomes crucial. Research shows that anthropogenic harvesting can cause phenotypic adaptive changes in exploited wild populations, particularly maturation at smaller size and younger age [4]. This framework provides essential insights for sustainable management practices that account for evolutionary consequences.

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

What constitutes a life history? An organism's life history encompasses the age- and stage-specific patterns of development, growth, maturation, reproduction, and lifespan [1] [2]. These include key events such as birth, weaning, maturation, first reproduction, number of offspring, level of parental investment, senescence, and death [1].

What are the core life history traits? Seven traits are traditionally recognized as central to life history theory [1]:

- Size at birth

- Growth pattern

- Age and size at maturity

- Number, size, and sex ratio of offspring

- Age- and size-specific reproductive investments

- Age- and size-specific mortality schedules

- Length of life

What is evolutionary fitness in life history context? In evolutionary terms, fitness is determined by how well an organism is represented in future generations, primarily through its rates of survivorship and reproduction [1]. Life history traits are the major components of fitness because they directly determine survival and reproductive success [2].

The Central Role of Trade-offs

Theoretical Basis of Trade-offs

Trade-offs represent the fundamental constraints that shape life history evolution [2]. They occur when an increase in one life history trait that improves fitness is coupled with a decrease in another trait that reduces fitness [2]. This concept is often visualized through the "finite pie" model - imagine a life history as a finite pie where different slices represent how an organism divides limited resources among growth, storage, maintenance, survival, and reproduction [2].

Without such constraints, evolution would produce "Darwinian demons" - hypothetical organisms that start reproducing immediately after birth, produce infinite offspring, and live forever [1] [2]. Since these organisms don't exist in nature, trade-offs must be operating to constrain evolutionary possibilities.

Major Life History Trade-offs

Several key trade-offs have been identified in life history research:

Reproduction vs. Survival: Increased current reproductive effort often comes at the cost of reduced future survival or reproduction [1] [2]. This forms the basis of the cost of reproduction hypothesis.

Current vs. Future Reproduction: Investments in current reproduction may reduce resources available for future reproductive events, creating a trade-off between immediate and delayed fitness benefits [1].

Offspring Quantity vs. Quality: Parents may face a choice between producing many offspring with minimal investment in each, or fewer offspring with greater parental investment per offspring [1].

Growth vs. Reproduction: Many organisms cannot simultaneously allocate maximum resources to both growth and reproduction, leading to a temporal separation of these life history phases [1].

Table 1: Major Life History Trade-offs and Their Ecological Implications

| Trade-off Type | Biological Mechanism | Population-Level Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Reproduction vs. Survival | Energetic costs of reproduction reduce resources for maintenance | Shapes pace-of-life continuum; influences senescence patterns |

| Current vs. Future Reproduction | Competitive allocation of limited resources | Determines reproductive scheduling and iteroparity vs. semelparity |

| Offspring Number vs. Size | Finite reproductive budget per episode | Affects population recruitment and offspring survival rates |

| Growth vs. Reproduction | Physiological partitioning of resources | Influences age and size at maturity, especially in harvested species |

Methodological Approaches and Challenges

Experimental Designs for Detecting Trade-offs

What are the primary methods for demonstrating trade-offs? Four main approaches are used to detect and quantify life history trade-offs [5]:

- Phenotypic Correlations: Measuring natural covariation between traits in populations

- Experimental Manipulations: Artificially altering one trait and observing consequences for other traits

- Genetic Correlations: Estimating genetic covariances between traits using quantitative genetics

- Correlated Responses to Selection: Observing how traits change in tandem during selection experiments

Why are trade-offs difficult to measure in practice? Individual heterogeneity in quality or resource access can mask underlying trade-offs [5]. For example, in bird populations, individuals that naturally produce larger clutches often have better survival, creating a positive correlation that obscures the underlying cost of reproduction [6]. Only when reproductive effort is experimentally increased beyond natural levels does the survival cost become apparent [6].

Key Methodological Considerations

How can researchers account for individual quality variation? Recent meta-analytic evidence suggests that genetic trade-offs may not be as common or easily quantifiable as often assumed [7]. A 2024 meta-analysis found an overall positive genetic correlation between survival and other life-history traits, counter to traditional predictions [7]. This highlights the importance of:

- Using both observational and experimental approaches

- Accounting for individual heterogeneity in resource acquisition

- Applying proper statistical controls for quality variation

- Considering environmental context in all analyses

Life History Evolution in Harvested Populations

Harvest-Induced Evolutionary Changes

How does harvesting affect life history evolution? Size-selective harvesting can drive evolutionary changes in life history traits, particularly toward earlier maturation and smaller size at maturity [4] [8]. Studies of northern freshwater fish populations reveal that exploitation leads to increased somatic growth, reduced age at maturity, and extended adult lifespans [8].

Table 2: Documented Life History Changes in Harvested Fish Populations

| Life History Trait | Response to Harvesting | Magnitude of Change | Management Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic growth rate | Increases with exploitation | 32 to 45 mm/year (~1.4-fold compensation) | May indicate growth overfishing |

| Age at maturity | Decreases with exploitation | From 11 to 8 years | Evolutionary impact requiring long-term management |

| Reproductive allocation | Varies with evolutionary trade-offs | Context-dependent | Requires population-specific monitoring |

| Adult lifespan | Increases with exploitation | Variable across systems | Complements age-truncation from harvest |

What factors influence harvesting-induced evolution? The evolutionary response depends on the type of life-history trade-off involved [4]. Research using predator-prey models has examined three recognized life-history costs of early maturation:

- Reduced fecundity

- Reduced growth

- Increased mortality

The evolutionarily stable maturation size under harvesting varies depending on which trade-off is operating and the predator's preferred size of prey [4].

Socio-Economic Dimensions in Human Populations

How does resource availability shape human life histories? Pre-industrial human populations demonstrate how resource variation affects life history traits and selection pressures [9]. Women from wealthier families showed:

- Higher age-specific survival throughout life

- Earlier reproduction

- More offspring over their lifetime

- Later reproductive cessation

- Better offspring survival to adulthood

The strength and direction of natural selection also varied by socio-economic class, with the strongest selection for earlier age at first reproduction occurring in the poorest wealth class [9].

Research Reagent Solutions: Methodological Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Methodological Approaches for Life-History Trade-off Research

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Primary Applications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Manipulation | Brood size manipulation | Quantifying costs of reproduction | [6] |

| Demographic Analysis | Path analysis of lifetime fitness | Measuring selection on multiple correlated traits | [9] |

| Quantitative Genetics | Animal model analyses | Partitioning genetic and environmental variance | [7] |

| Population Modeling | Euler-Lotka equation | Predicting fitness consequences of trait changes | [2] |

| Long-term Monitoring | Cohort tracking in natural populations | Documenting trait changes over time | [8] |

| Urea N-15 | Urea N-15, CAS:2067-80-3, MF:CH4N2O, MW:62.042 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Adrenic Acid | Adrenic Acid|Research Biomarker|CAS 28874-58-0 | Adrenic acid is a key omega-6 fatty acid and promising biomarker for metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurological disease research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Conceptual Framework and Experimental Workflows

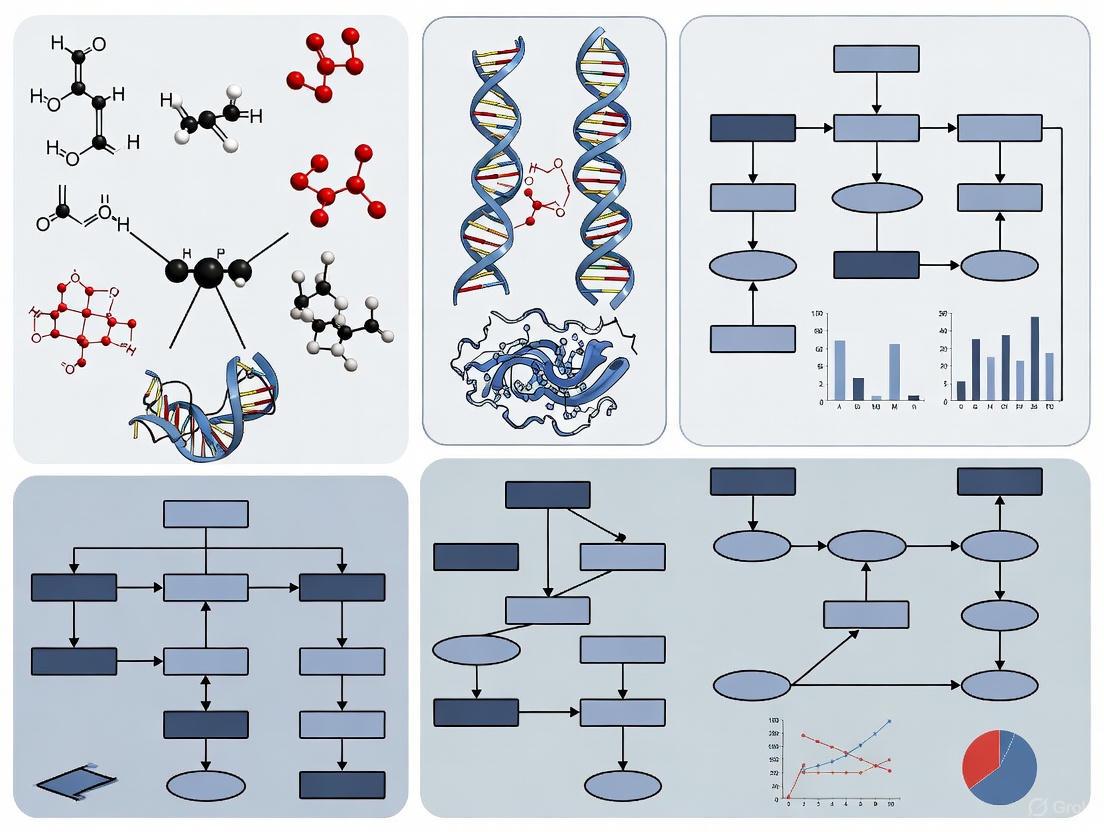

Diagram 1: Life History Research Workflow

Diagram 2: Resource Allocation Trade-offs

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it difficult to detect clear trade-offs between reproduction and survival in wild populations? Individual variation in quality often masks underlying trade-offs [5] [6]. High-quality individuals with better access to resources can invest more in both reproduction and survival, creating positive correlations that obscure the fundamental trade-offs [6]. Experimental manipulations that push individuals beyond their natural reproductive effort are often needed to reveal these costs [6].

How quickly can harvesting induce evolutionary changes in life histories? Documented changes can occur relatively quickly. Studies of lake trout show that changes in growth rates and age at maturity can be detected across exploitation gradients, with ~1.4-fold growth compensation observed from pristine to fully exploited conditions [8]. These changes represent a combination of plastic responses and evolutionary adaptations.

What is the evidence for genetic trade-offs from meta-analyses? Recent comprehensive meta-analyses present surprising findings. A 2024 analysis found overall positive genetic correlations between survival and other life-history traits, with no evidence for negative genetic correlations between non-survival traits [7]. This suggests genetic trade-offs may be less common than traditionally assumed in animal populations.

How does resource availability affect human life history trade-offs? In pre-industrial human populations, wealthier women showed different life history patterns and selection pressures compared to poorer women [9]. The poorest women experienced the strongest selection for earlier reproduction, while wealthier women showed selection for delayed reproductive cessation [9]. This demonstrates how socio-economic factors shape evolutionary trajectories in humans.

What management approaches account for life history evolution? Evolutionarily enlightened management considers both demographic and evolutionary impacts of harvesting [4] [8]. This includes:

- Monitoring changes in maturation timing and size

- Considering the type of life-history trade-offs operating in specific populations

- Implementing harvest strategies that consider evolutionary consequences

- Recognizing that compensation patterns vary among species and populations

Defining Fisheries-Induced Evolution (FIE) and Its Prevalence

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is Fisheries-Induced Evolution (FIE)? Fisheries-induced evolution (FIE) is the microevolution of an exploited aquatic population caused by artificial selection from fishing practices. It occurs when fishing imposes selective mortality, permanently removing certain genetic traits from the population and allowing others to proliferate. This process fundamentally alters population gene frequency, often countering natural life-history patterns by favoring traits such as earlier sexual maturation and smaller body sizes in matured fish [10].

What is the primary cause of FIE? The primary cause is direct selective mortality from fishing. This includes selection based on biological traits through fishery management regulations (e.g., minimum landing size) and gear selectivity. For instance, centuries of selectively harvesting larger Atlantic cod have shifted life-history patterns, resulting in earlier maturation at smaller sizes [10].

Is there experimental evidence supporting FIE? Yes, experimental approaches have provided crucial evidence. Common garden and selection experiments have demonstrated that traits like growth rate, age-at-maturation, and behavior can evolve in response to selective pressures mimicking fishing. These controlled studies are essential for disentangling genetic changes from environmental influences [11].

Why is it difficult to detect FIE in wild populations? Detecting FIE is challenging because the traits influenced, such as body size and age-at-maturation, are also highly phenotypically plastic and sensitive to environmental factors like temperature and food availability. Disentangling these genetic and environmental causes requires long-term data and sophisticated statistical methods like Probabilistic Maturation Reaction Norms (PMRNs) [12].

Can FIE be reversed? The potential for and rate of reversibility of FIE are active research areas. Some studies suggest that evolutionary changes might persist for long periods even after fishing ceases, while others indicate that removing the selective pressure could allow for gradual recovery. The reversal likely depends on the species, the intensity and duration of fishing, and the genetic constraints of the population [13] [14].

Troubleshooting Common Research Challenges

Challenge: Disentangling genetic and environmental effects on phenotypic traits.

- Problem: Observed changes in traits like body size could be due to evolution (genetic) or to plastic responses to environmental changes (e.g., density, temperature).

- Solution: Implement a Common Garden Experiment.

- Methodology: Collect offspring from multiple populations subjected to different fishing pressures. Rear them under identical, controlled environmental conditions for one or more generations.

- Interpretation: Phenotypic differences that persist under these common conditions are likely to have a genetic basis, providing evidence for local adaptation and evolvability [11].

Challenge: Simulating the evolutionary impact of specific fishing selection pressures.

- Problem: How to directly test the cause-and-effect relationship between a specific selective pressure (e.g., size-selective harvest) and evolutionary response.

- Solution: Conduct a Selection Experiment.

- Methodology: Establish replicate laboratory or mesocosm populations. Apply a consistent selection pressure (e.g., removing the largest individuals each generation) over multiple generations. Compare the evolutionary trajectory with control populations that are harvested randomly.

- Interpretation: This approach directly demonstrates rapid life-history evolution and can reveal how a cluster of genetically correlated traits (physiology, behavior, reproduction) diverge simultaneously [11].

Challenge: Accounting for "cryptic" selective pressures beyond body size.

- Problem: Focusing only on size may overlook other traits that influence capture vulnerability, such as physiology and behavior.

- Solution: Integrate physiological and behavioral metrics.

- Methodology: Measure traits like standard metabolic rate (SMR), aerobic scope, stress responsiveness, and boldness in individuals. Use telemetry or controlled fishing trials to correlate these traits with capture vulnerability.

- Interpretation: This provides a more mechanistic understanding of how fishing acts as a selective agent. For example, fish with higher SMR or boldness may be more active and vulnerable to passive gears like gillnets [13].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for FIE Research

The following table details key reagents, model organisms, and methodological tools used in FIE research.

| Research Solution | Function & Application in FIE Research |

|---|---|

| Common Garden Design | A controlled environment protocol to eliminate phenotypic plasticity, allowing the isolation and measurement of genetic differences among populations [11]. |

| Quantitative Genetic Models | Statistical models used to predict evolutionary trajectories by estimating heritability of traits and genetic correlations between them [14]. |

| Probabilistic Maturation Reaction Norms (PMRNs) | A statistical method used to estimate the probability of an individual maturing at a given age and size, helping to disentangle evolutionary changes from plastic responses [12]. |

| Individual-Based Simulation Models | Computer models that simulate the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of a population by tracking individuals with unique genotypes, used to project long-term FIE impacts [14]. |

| Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) | A key model organism in FIE research due to its historical importance, data-rich history, and documented phenotypic changes, making it a classic case study [10] [14] [12]. |

| Atlantic Silverside (Menidia menidia) | A small fish model used in selection experiments due to its short generation time, demonstrating rapid evolution of growth rate and other life-history traits in response to size-selective harvest [11]. |

Quantitative Data on FIE

The table below summarizes key traits affected by fisheries-induced evolution and their documented heritability, which is a measure of their evolutionary potential.

| Trait Category | Specific Trait | Example Species | Heritability (h²) / Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life History | Age-at-Maturation | Atlantic Cod, North Sea Plaice | Phenotypic shifts consistent with theory; heritability typically 0.2-0.3 [12]. |

| Life History | Size-at-Maturation | Atlantic Cod, Pacific Salmon | Decreases widely observed; heritable component [10] [12]. |

| Physiology | Standard Metabolic Rate | Various fish species | Heritability estimates range from ~0.1 to 0.7, making it a potential target for selection [13]. |

| Physiology | Stress Responsiveness | European Seabass (D. labrax) | Heritability estimates range from 0.08 to 0.34 [13]. |

| Behavior | Boldness/Aggression | Rainbow Trout, Guppies | Behavioral traits are heritable and can influence gear vulnerability (e.g., bold individuals are more catchable) [10] [13]. |

| Fecundity | Egg Production & Viability | Atlantic Cod | Reduced fecundity observed as a correlated response to smaller body size and earlier maturation [10]. |

Experimental Workflows and Conceptual Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for a Selection Experiment

This diagram visualizes the methodology for a controlled selection experiment, a key protocol for establishing causality in FIE.

Conceptual Diagram of FIE Mechanisms and Consequences

This diagram outlines the core causal pathway of fisheries-induced evolution and its potential consequences for fish populations.

Linking Harvest Selection Pressure to Life-History Shifts

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is fisheries-induced evolution (FIE) and how does it relate to harvest selection pressure?

A: Fisheries-induced evolution (FIE) occurs when intensive, selective fishing causes genetic changes in heritable traits of exploited stocks. Harvest selection pressure typically acts in reverse to natural selection, favoring individuals with specific life-history traits, such as younger age and smaller size at maturation, leading to fundamental shifts in population characteristics over time [15].

Q2: What are the primary life-history shifts observed in harvested populations?

A: The most common evolutionary trajectory is a shift toward a 'live fast, die young' strategy. This includes [15]:

- Earlier maturation and reproductive investment at a younger age.

- Reduced growth rates or a shift in energy allocation away from growth.

- Smaller adult body sizes over generations.

Q3: Why is size-selective harvesting a major driver of FIE?

A: Size-selective harvesting, often mandated by management regulations like minimum landing sizes, exposes larger individuals to disproportionately high mortality rates. Since body size is a central biological trait correlated with maturity, fecundity, and behavior, selecting against large body size directly alters the gene pool, favoring genes for slower growth and earlier reproduction [15].

Q4: What are the broader ecosystem consequences of these life-history shifts?

A: Life-history shifts in harvested species can propagate through marine food webs, causing [15]:

- Trophic Cascades: Altered predator-prey interactions that can impact species at multiple trophic levels.

- Shrinking Trophic Niche: Smaller body sizes lead to a narrower dietary range, reducing resilience to prey fluctuations.

- Biodiversity Loss: Weakened recovery potential of depleted stocks can accelerate the loss of biodiversity.

Q5: How can researchers experimentally investigate FIE?

A: Controlled laboratory experiments using model fish species (e.g., medaka, Oryzias latipes) are key. Researchers can apply artificial size-selective mortality over multiple generations to create distinct selection lines (e.g., large-breeder vs. small-breeder lines) and study the resulting evolutionary and demographic changes under different densities and size structures [16].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Challenges

Issue 1: Differentiating Genetic Evolution from Phenotypic Plasticity

A common challenge is determining whether observed trait changes are genuine genetic evolution or a plastic response to environmental factors like resource availability.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Step | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trait shifts occur rapidly (within 1-2 generations). | Phenotypic plasticity (non-heritable response). | Common Garden Experiment: Rear offspring from harvested and control populations under identical, controlled conditions. | If differences persist in a common environment, it provides strong evidence for genetic change [15]. |

| Trait shifts are consistent across varying environments. | Genetic evolution. | Compare trait values in populations from different fishing pressures under multiple laboratory conditions. | Consistent differences support FIE. |

| High variability in trait values within a population. | High phenotypic plasticity or demographic effects. | Analyze individual-level data and perform quantitative genetic modeling. | Statistical models can help partition variance into genetic and environmental components [15]. |

Issue 2: Low Reproductive Output in Experimental Populations

A decline in population fitness, such as reduced spawning or egg viability, can complicate experiments.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Step | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased egg production or spawning frequency. | Energy reallocation due to selection for early maturity. | Monitor energy budgets (e.g., gonad vs. somatic tissue weight). | Account for this as an evolutionary outcome in experimental design [16]. |

| Poor egg viability or larval survival. | Inbreeding depression or unintentional selection for lower gamete quality. | Track genetic diversity (e.g., using microsatellites) and compare with control lines. | Maintain large, outbred experimental populations to minimize inbreeding effects. |

| General decline in population health. | Inappropriate density in experimental tanks. | Test replicate populations at high vs. low density. | Adjust density to levels that do not inhibit growth or reproduction, as density can mask evolutionary effects [16]. |

Issue 3: Confounding Effects of Demography and Evolution

The impacts of simply removing large individuals (a demographic effect) can be confused with evolutionary change.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Step | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid body size truncation after harvesting begins. | Demographic truncation (loss of large individuals from the population). | Use age-structured population models to project expected demographic changes. | Compare observed trait changes to model predictions that include only demographic effects [15]. |

| Slow or no recovery of traits after harvesting stops. | Evolutionary change that is not immediately reversible. | Continue monitoring populations for multiple generations after ceasing selective pressure. | A lack of recovery suggests a genetic legacy that may require specific management interventions [15]. |

Quantitative Data on Selection Pressure and Fitness

Table 1: Documented Life-History Changes in Experimentally Harvested Medaka (Oryzias latipes) [16]

| Selection Line | Maturation Age | Maturation Size | Somatic Growth Rate | Probability of Reproduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large-Breeder Line | Later | Larger | Faster | Lower (for small-sized females) |

| Small-Breeder Line | Earlier | Smaller | Slower | Higher (for small-sized females) |

| Control Line | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate |

Table 2: Contrasting Natural and Fisheries-Induced Selection Pressures [15]

| Selective Agent | Direction of Selection on Body Size | Direction of Selection on Maturation Age | Expected Life-History Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Selection | Favors larger size | Favors older age | Slower life history, larger maximum size |

| Fisheries-Induced Selection | Favors smaller size | Favors younger age | Faster life history, smaller maximum size |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Establishing Size-Selective Breeding Lines in Fish

Objective: To experimentally simulate harvest-induced evolution and create distinct breeding lines for studying life-history shifts.

Materials:

- Model fish species (e.g., Medaka - Oryzias latipes)

- Recirculating aquarium systems with controlled temperature and light cycles

- Anesthetic (e.g., MS-222)

- Digital balance and measuring tools

- Breeding tanks and egg collection apparatus

Methodology [16]:

- Founder Population: Start with a large, genetically diverse founder population of fish. Randomly divide them into three selection lines: large-breeder, small-breeder, and control.

- Selection Regime:

- Large-Breeder Line: In each generation, selectively remove the largest 25% of individuals from the breeding pool, simulating a fishery that avoids taking small fish.

- Small-Breeder Line: In each generation, selectively remove the smallest 25% of individuals, simulating typical size-selective harvest.

- Control Line: Randomly remove 25% of individuals, regardless of size, to control for demographic effects and random genetic drift.

- Breeding: Allow the remaining fish in each line to reproduce randomly. Collect eggs and rear the offspring under standardized, common conditions.

- Data Collection: Over multiple generations (e.g., 3-5+), track key life-history traits in all lines:

- Age and size at first maturation

- Somatic growth rate

- Fecundity (number of eggs)

- Offspring viability

- Analysis: Compare the trajectories of life-history traits between the selection lines and the control line using statistical models (e.g., mixed-effects models) to isolate the evolutionary signal.

Visualization: Experimental Workflow for FIE Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Experimental FIE Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Model Organism (Medaka) | Small, fast-generation teleost fish ideal for multigenerational evolutionary studies. | Oryzias latipes; has a sequenced genome and well-established husbandry protocols [16]. |

| Common Garden Setup | Controlled aquarium environments to standardize conditions and isolate genetic effects from plastic responses. | Recirculating systems with precise temperature, light, and feeding control are essential [16]. |

| Anesthetic (MS-222) | To safely immobilize fish for non-lethal measurements like length and weight. | Tricaine methanesulfonate; standard for handling aquatic organisms. |

| Genetic Markers | To monitor and quantify genetic diversity, effective population size, and inbreeding. | Microsatellites or Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) for population genetic analysis. |

| Image Analysis Software | For precise, non-invasive measurement of fish body size and shape from photographs. | Helps reduce handling stress during data collection. |

| Statistical Software (R) | For complex data analysis, including mixed-effects models and quantitative genetics. | Packages like glmmTMB, lme4, and nlme are commonly used [16]. |

| 1-Cinnamoylpyrrolidine | 1-Cinnamoylpyrrolidine, CAS:52438-21-8, MF:C13H15NO, MW:201.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Quinamine | Quinamine|CAS 464-85-7|Research Chemical |

The Fast-Slow Life-History Continuum in Exploited Species

What is the fast-slow life-history continuum?

The fast-slow continuum is a framework for classifying organisms based on key life-history traits. Species are arranged along a spectrum from "fast" strategies—characterized by small body size, short lifespan, early reproduction, and high fecundity—to "slow" strategies, which display the opposite characteristics: large body size, long lifespan, late maturation, and low fecundity [17] [18]. This continuum helps predict population responses to natural and anthropogenic pressures [17].

Why is this concept critical for managing exploited populations?

Life-history strategy determines a species' resilience and sensitivity to perturbations. In the marine environment, "slow" species are disproportionately affected by fishing pressure, leading to more severe population declines compared to "fast" species [17]. Understanding a species' position on this continuum is therefore essential for sustainable management and preventing fishery-induced evolution [19].

What are classic examples of fast and slow species?

Cephalopods (e.g., squid, octopus) are typical fast-strategy species. They have short life spans (1-2 years), high population growth rates, and high fecundity [17]. Elasmobranchs (e.g., sharks, rays) are typical slow-strategy species. They are long-lived, slow-growing, late-maturing, and have low reproductive rates [17].

Troubleshooting Common Research Challenges

Issue: Unexpected Population Decline in a Harvested Species

Q: My model shows a steep decline in a commercially harvested species, but I expected it to be sustainable. What might be wrong?

A: This is a common issue when the life-history strategy of the target species is mismatched with the harvesting regime.

- Diagnosis Checklist:

- Confirm Species Strategy: First, verify the life-history traits of your species against the fast-slow continuum (see Table 1). Are you applying a high harvesting pressure to a slow-strategy species? [17]

- Check for Evolutionary Traps: Intensive, size-selective harvesting that targets larger, older fish can create an evolutionary pressure favoring individuals that mature earlier and at a smaller size. This can lead to long-term changes in the population's genetic makeup, reducing yield and resilience [19].

- Review Model Parameters: Ensure your model correctly incorporates age at first reproduction and fecundity-at-age. For slow species, even low harvesting rates on adults can be unsustainable [19].

Issue: Differentiating Environmental from Harvesting Effects

Q: I'm observing fluctuations in species abundance. How can I determine if the cause is environmental change or fishing pressure?

A: Fast and slow species respond differently to these drivers, providing a diagnostic tool.

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Analyze Response Patterns: Compare population trends of co-occurring fast and slow species.

- If only slow-strategy species (e.g., elasmobranchs) are declining, fishing exploitation is the likely primary driver [17].

- If fast-strategy species (e.g., cephalopods) show strong short-term or seasonal oscillations, the cause is more likely environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, productivity) [17].

- Statistical Modeling: Use Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) to test the separate and interactive effects of environmental variables (temperature, productivity) and fishing mortality (e.g., catch per unit effort). The seminal study by Quetglas et al. (2016) found that, apart from depth, cephalopod and elasmobranch abundances were exclusively affected by environmental conditions and fishing exploitation, respectively [17].

- Analyze Response Patterns: Compare population trends of co-occurring fast and slow species.

Issue: Model Fails to Predict Collapse in a "Sustainable" Fishery

Q: My age-structured model suggested a sustainable fishery, but the population collapsed. What model component might I be missing?

A: Many traditional models focus on a fixed life-history trait, but harvesting can induce evolution.

- Solution: Incorporate Evolutionary Dynamics.

- Model a Variant Group: Expand your model to include a "variant" sub-population with a different life-history trait, such as an earlier age at first reproduction. A resident group might first reproduce at age 3, while a variant group reproduces at age 2 [19].

- Simulate Selective Pressure: Apply your harvesting strategy. Models show that harvesting large adults can selectively favor the variant group, causing the resident strategy to be replaced. This evolutionary shift can lead to a less productive population and eventual collapse, even if the harvest initially seemed sustainable [19].

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Age-Structured Population Modeling for Harvest-Induced Evolution

This protocol is based on the discrete-time model used to study the evolution of age at first reproduction under harvesting [19].

1. Research Question: How does age-selective harvesting influence the evolution of age at first reproduction in an exploited population?

2. Model Structure:

- Age Classes: Structure the population into four distinct age classes:

- Nâ‚€: Newborns (age 0-1 year)

- Nâ‚: Juveniles (age 1-2 years)

- Nâ‚‚: Small Adults (age 2-3 years)

- N₃: Large Adults (age ≥ 3 years)

- Life-History Traits: Define two sub-populations:

- Resident Type: First reproduces as a large adult (probability

γ). - Variant Type: First reproduces as a small adult (probability

1-γ).

- Resident Type: First reproduces as a large adult (probability

3. Core Model Equations: The population dynamics for a single type can be described by the following system of equations [19]:

4. Parameterization: Table 1: Key Parameters for the Age-Structured Model [19]

| Parameter | Biological Meaning | Typical Value/Range |

|---|---|---|

f₂, f̃₃, f₃ |

Fecundity (number of offspring) for small adults, large adults that first reproduced as small adults, and large adults that first reproduced as large adults, respectively. | Model-specific |

sâ‚€, sâ‚, sâ‚‚, s₃ |

Annual survival rates for newborns, juveniles, small adults, and large adults, respectively. | 0.1 - 0.9 (density-dependent for sâ‚€) |

hâ‚, hâ‚‚, h₃ |

Harvesting mortality rates applied to juveniles, small adults, and large adults, respectively. | 0.0 - 1.0 |

γ |

Probability of first reproducing as a small adult. | 0.0 (pure resident) to 1.0 (pure variant) |

m |

Constant for density-dependent survival in the Monod function. | Model-specific |

5. Simulation and Analysis:

- Run the model for the resident and variant populations separately or in competition under different harvesting scenarios (

hâ‚,hâ‚‚,h₃). - Track the population trajectories and the ratio of variant-to-resident individuals over time.

- Key Outcome: The model demonstrates that selectively harvesting large adults (

h₃> 0) can cause the variant (early reproducer) type to evolve and dominate the population [19].

Protocol 2: Contrasting Response Analysis Using Generalized Addive Models (GAMs)

This protocol outlines the methodology for empirically testing the differential responses of fast and slow species to environmental and anthropogenic drivers [17].

1. Research Question: How do the abundances of cephalopods (fast) and elasmobranchs (slow) respond to fishing exploitation and environmental conditions?

2. Data Collection:

- Abundance Data: Collect standardised abundance data (e.g., numbers per unit area) from scientific trawl surveys. The MEDITS survey protocol is a leading example [17].

- Environmental Data: Match each survey station with concurrent data for depth, bottom temperature, and productivity (e.g., chlorophyll-a concentration) [17].

- Fishing Exploitation Data: Obtain data on fishing pressure, such as local fishing effort or landings per unit area.

3. Statistical Modeling with GAMs:

- Use GAMs to model species abundance as a flexible function of the predictors.

- A simplified model structure:

Abundance ~ s(Temperature) + s(Productivity) + s(Depth) + s(Fishing_Effort) - Run separate models for cephalopod and elasmobranch species.

4. Interpretation of Results:

- Expect to find that cephalopod abundance is significantly influenced by environmental predictors (temperature, productivity) [17].

- Expect to find that elasmobranch abundance is significantly influenced by fishing effort [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Life-History and Fisheries Population Dynamics Research

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Trawl Surveys (e.g., MEDITS) | Provides structured, repeatable collection of fishery-independent data on species abundance and distribution by depth stratum [17]. | Essential for generating the response variable (abundance/biomass) for population models and GAM analyses. |

| Generalized Additive Models | A statistical modeling technique that fits smooth, non-parametric functions to data, ideal for capturing complex, non-linear relationships [17]. | Used to analyze and visualize the relationship between species abundance and environmental/harvesting drivers. |

| Age-Structured Population Models | Mathematical frameworks that track population numbers across discrete age classes over time, incorporating survival, fecundity, and harvesting [19]. | The core tool for projecting population dynamics, testing harvesting scenarios, and modeling evolutionary consequences. |

| Life-History Trait Databases | Curated repositories of species-specific data on traits like age at maturity, lifespan, fecundity, and growth parameters. | Used to classify species on the fast-slow continuum and to parameterize population models. |

| Thioetheramide-PC | Thioether Amide PC|Phospholipase A2 Inhibitor | Thioether amide PC is a non-hydrolyzable Phospholipase A2 inhibitor for biochemical research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2,3,4'-Trihydroxy-3',5'-dimethoxypropiophenone | 2,3,4'-Trihydroxy-3',5'-dimethoxypropiophenone|CAS 33900-74-2 |

Conceptual and Workflow Visualizations

Fast-Slow Continuum Conceptual Framework

Age-Structured Model Workflow

Harvesting-Induced Evolutionary Shift

Genetic Variation and Heritability of Life-History Traits

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why is my estimate of heritability for a life-history trait unexpectedly low or statistically insignificant?

Low heritability estimates can arise from several sources. The table below outlines common issues and their solutions.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Quality | Censored data or incomplete life-history records [20]. | Perform analyses using both pairwise and listwise omission of missing values to check for consistency [20]. |

| Statistical Power | Sample size is too small, or the pedigree lacks diverse relationships [20]. | Use an "animal model" framework (REML) that incorporates all available pedigree relationships (e.g., parents, siblings, half-siblings, grandparents) to maximize power [20]. |

| Model Specification | Failure to control for shared environmental or cultural effects, inflating resemblance among relatives [20]. | In the statistical model, include fixed or random effects to account for common environments (e.g., geographic parish, shared household) [20]. |

| Trait Definition | The trait is not defined to minimize non-genetic influences. | For fitness measures like Lifetime Reproductive Success (LRS), use the number of offspring raised to adulthood (e.g., 15 years) rather than just the number born [20]. |

FAQ 2: How can I accurately test for genetic trade-offs (negative genetic correlations) between life-history traits?

Detecting genetic trade-offs, like the one between early reproduction and longevity, is methodologically challenging.

- Problem: The trade-off is masked by individual quality or environmental variation, where higher-quality individuals have both higher reproduction and longer life, creating a positive phenotypic correlation [20].

- Solution: Use a Restricted Maximum-Likelihood (REML) animal model to estimate genetic correlations. This method uses the entire pedigree to separate the additive genetic variance (which reveals the underlying trade-off) from environmental and residual variances [20]. A study on preindustrial Finns used this to reveal a strong positive genetic correlation between female age at first reproduction and longevity, indicating a reduced lifespan for those who started breeding early [20].

FAQ 3: What are the primary sources of error when calculating individual fitness in longitudinal studies?

- Relying solely on Lifetime Reproductive Success (LRS): LRS ignores the timing of reproduction. In a growing population, offspring produced earlier contribute more to fitness than those produced later [20].

- Solution: Calculate a rate-sensitive fitness measure, such as individual lambda (λ), which incorporates both fecundity and the timing of reproductive events [20]. This can be calculated using specialized MATLAB scripts or other statistical software [20].

FAQ 4: My experiment is failing to yield reproducible results. What is a systematic approach to troubleshooting?

Follow these steps to diagnose and resolve experimental issues [21] [22]:

- Identify the Problem: Isolate the specific variable or part of the experiment that is not working. This may require multiple re-runs [21].

- Research: Investigate potential solutions by reading literature and consulting with colleagues who may have faced similar issues [21].

- Create a Game Plan: Develop a detailed, written plan for troubleshooting, ensuring you have all necessary reagents and materials [21].

- Implement the Plan: Execute your plan, meticulously recording all progress and adjustments in a lab notebook [21].

- Solve and Reproduce: Once the problem is resolved, repeat the experiment to confirm that the solution consistently produces the desired results [21].

Quantitative Data on Life-History Trait Heritability

The following data, derived from a preindustrial Finnish population using REML animal models, provides key benchmarks for heritability and genetic correlations in a human population under pre-modern conditions [20].

Table 1: Heritability Estimates of Life-History and Fitness Traits

| Trait | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|

| Fecundity (number of children born) | High | Not High |

| Interbirth Interval (months) | High | N/A |

| Age at First Reproduction (years) | High | Not High |

| Age at Last Reproduction (years) | High | N/A |

| Adult Longevity (years) | High | Not High |

| Lifetime Reproductive Success (LRS) | High | Not High |

| Individual Lambda (λ) | High | Not High |

Table 2: Key Genetic Correlations Between Female Life-History Traits

| Trait 1 | Trait 2 | Genetic Correlation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at First Reproduction | Adult Longevity | Strong Positive | Genotypes for earlier reproduction correlate with genotypes for shorter lifespans, revealing a cost of reproduction [20]. |

| Interbirth Interval | Adult Longevity | Strong Positive | Genotypes for more frequent breeding (shorter intervals) correlate with genotypes for shorter lifespans [20]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Estimating Heritability using an Animal Model

This methodology is adapted from the study on preindustrial Finns [20].

Pedigree and Life-History Data Collection:

- Source: Gather detailed genealogical records spanning multiple generations. For the Finnish study, this included four generations from 1745-1900 [20].

- Data Points: For each individual, record complete life-history data: birth date, death date, and all reproductive events (births of all children) [20].

- Inclusion Criteria: For reproductive traits, include only individuals who reproduced at least once. For age at last reproduction, include only females who survived to at least 45 and were not widowed before then [20].

Trait Calculation:

- Lifetime Reproductive Success (LRS): The total number of children produced that survived to adulthood (e.g., 15 years) [20].

- Individual Lambda (λ): A rate-sensitive fitness measure calculated using matrix population models, incorporating the timing and number of offspring raised to adulthood. This can be computed with software like MATLAB [20].

- Other Traits: Calculate fecundity, age at first reproduction, mean interbirth interval, age at last reproduction (females only), and adult longevity (for all individuals surviving past 15) [20].

Statistical Analysis with REML Animal Model:

- Framework: Use a Restricted Maximum-Likelihood (REML) approach within an "animal model" framework.

- Model Input: The model uses the entire pedigree structure to partition the phenotypic variance of a trait into additive genetic variance (the variance due to breeding values) and residual variance (which includes environmental effects) [20].

- Heritability Calculation: Heritability (h²) is calculated as Additive Genetic Variance / Total Phenotypic Variance.

- Genetic Correlations: The model can be extended to a multivariate framework to estimate genetic correlations between two traits by analyzing their additive genetic covariances [20].

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Relationships

Genetic Analysis of Life-History Traits

Genetic Constraints in Life-History Evolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Genetic Studies of Life-History Traits

| Item / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Genealogical Database | Provides the multi-generational pedigree structure and life-history data (birth, death, reproduction) necessary for constructing relatedness matrices and calculating traits [20]. |

| REML Animal Model Software | Specialized statistical software (e.g., ASReml, MCMCglmm in R, WOMBAT) used to perform the complex variance component analysis required for estimating heritabilities and genetic correlations [20]. |

| Molecular Techniques (e.g., DNA microarrays) | Used in modern studies to directly analyze DNA, identify SNPs, and understand the molecular basis of observed genetic variation and heritability [23]. |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | A digital system for standardizing data entry, managing complex pedigree and trait data, ensuring version control, and maintaining a reliable audit trail, which reduces human error [24]. |

| Ethylene glycol-d4 | Ethylene glycol-d4, CAS:2219-51-4, MF:C2H6O2, MW:66.09 g/mol |

| 1,4-Dibromobutane-d8 | 1,4-Dibromobutane-d8, CAS:68375-92-8, MF:C4H8Br2, MW:223.96 g/mol |

Detecting and Projecting Evolutionary Impacts: Models and Metrics

Quantitative Genetic and Individual-Based Modeling Approaches

FAQ: Core Concepts and Applications

Q1: What are the key differences between quantitative genetic and individual-based modeling approaches for studying life-history evolution?

A1: These approaches model evolution at different biological levels and have distinct strengths. The table below summarizes their core characteristics:

| Feature | Quantitative Genetic Models | Individual-Based Models (IBMs) |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Level | Population-level parameters (e.g., genetic variances, means). [25] | Individual organisms and their traits. Also known as Individual-Based Models (IBMs) in ecology. [26] |

| Key Parameters | Heritability, genetic correlations, breeding values, selection differentials. [25] | Individual life-history traits (e.g., size, age), behaviors, and local interactions. [27] [26] |

| Typical Output | Predicts changes in mean trait values and genetic variance over time. [25] [28] | Emergent population-level patterns (e.g., size structure, spatial distribution) from individual interactions. [26] [29] |

| Strengths | Efficient for projecting rates of evolutionary change over generations. [25] | High realism; can incorporate complex inheritance, plasticity, density-dependence, and stochasticity. [27] [26] |

| Common Uses | Predicting evolutionary response to selection, e.g., harvest-induced evolution. [27] [30] | Studying ecological and evolutionary dynamics in realistically structured populations. [27] [29] |

Q2: How can these modeling approaches be integrated?

A2: Eco-genetic modeling is a powerful framework that combines both approaches. It uses individual-based simulations to represent the ecological dynamics of a population with age and size structure, density dependence, and stochasticity. Crucially, it incorporates quantitative genetic principles, such as probabilistic inheritance of quantitative traits, genetic variances, and covariances, to predict evolutionary change. This integration allows for the study of multi-trait life-history evolution in realistically structured populations over contemporary time scales. [27]

Q3: Why is modeling life-history evolution crucial for managing harvested populations?

A3: Intensive harvesting acts as a strong selective force, leading to rapid evolutionary changes in life-history traits. For example, models have predicted and evidence has corroborated that fishing can induce genetic reductions in age and size at maturation and alter growth capacity. These evolutionary changes are often masked by plastic responses and can show little sign of reversal even after harvesting stops, threatening long-term population sustainability and productivity. Models provide testable predictions to guide evolutionarily sustainable resource management. [27] [30]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Modeling Challenges

Q1: My model shows excessively rapid evolutionary change. What could be wrong?

A1: This often points to issues with the genetic parameters or selection intensity in your model.

- Check Heritability Values: Ensure the input heritabilities for life-history traits are realistic (often in the range of 0.2-0.3). Overly high values will accelerate evolutionary rates. [27]

- Review Genetic Correlations: Ignoring negative genetic correlations between traits (e.g., between growth and reproductive investment) can lead to unrealistic evolutionary trajectories. Correlations impose trade-offs and constrain the speed and direction of evolution. [27]

- Calibrate Selection Intensity: The intensity of selection imposed by the harvest (e.g., fishing mortality rate) must be accurately parameterized. Overestimation will drive unrealistically fast evolution. [30]

Q2: My individual-based model is producing unrealistic population dynamics or crashes. How can I diagnose the issue?

A2: This can stem from several sources related to the implementation of individual-level processes.

- Verify Density Dependence: A common error is incorrect implementation or strength of density-dependent survival, growth, or fecundity. This is a key stabilizing mechanism in population models. [27]

- Check Stochasticity: Ensure that demographic stochasticity (random birth and death events) is correctly implemented. Its impact is greater at small population sizes and can lead to extinction if not properly balanced. [27] [29]

- Validate Inheritance Rules: In IBMs with genetics, errors in the rules for probabilistic inheritance of traits can rapidly erode genetic diversity or create inviable offspring, destabilizing the population. [27]

- Use a Unified Framework: To avoid algebraic and implementation errors, consider using a unified mathematical and software framework designed for analyzing IBMs, which can help ensure model consistency. [29]

Q3: How do I effectively model the interaction between genetic evolution and phenotypic plasticity?

A3: This is a key challenge in eco-evolutionary dynamics.

- Explicitly Model the Reaction Norm: Represent key life-history traits (like age at maturation) as plastic reaction norms—the genetically determined set of phenotypes an individual can express across different environments. Selection then acts on the parameters of these reaction norms. [27]

- Partition Phenotypic Change: Design your model and analysis to distinguish the plastic response within a generation from the genetic evolutionary response across generations. In harvested populations, plastic changes can phenotypically mask the underlying evolutionary changes. [27]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building an Eco-Genetic IBM for a Harvested Fish Population

This protocol outlines the steps for creating an individual-based model that incorporates quantitative genetics to study harvest-induced evolution, based on the approach used for Atlantic cod. [27]

1. Define Individual State Variables:

- Mandatory Variables: Unique ID, age, body size (e.g., length), sex, maturation status (mature/immature).

- Genetic Architecture: For a growth-related trait like asymptotic length (

L_inf), simulate it as a polygenic trait. For example, assign each individual a genotypic value based on the sum of alleles at 10 diploid loci, plus a small random environmental deviation to achieve a realistic heritability (~0.2-0.3). [27]

2. Implement Individual Processes (Annual Cycle):

- Growth: Model growth using a von Bertalanffy growth function, where an individual's genetically influenced

L_infand growth coefficientkdetermine its annual size increase. [27] [30] - Maturation: Make maturation probability a function of age and size, potentially linked to the individual's genetic traits.

- Reproduction: Mature individuals produce offspring based on a fecundity-size relationship. Assigning parents and implementing inheritance is critical.

- Mortality: Apply natural mortality rates. Then, implement harvest mortality based on a defined selection policy (e.g., a minimum-size limit).

3. Implement Inheritance:

- Parental Allocation: Each offspring is assigned one male and one female parent from the pool of mature individuals.

- Genotype Construction: For each genetic locus, the offspring randomly receives one allele from each parent. This process is repeated for all loci governing the trait. [27]

- Phenotype Calculation: The offspring's genotypic value is calculated from its alleles, and an environmental value is added to create its phenotypic value for the trait.

4. Set Up Model Environment and Execution:

- Initialization: Create a starting population with a stable age/size distribution and realistic genetic variation.

- Density Dependence: Implement density-dependent survival or growth, typically at the juvenile stage, to regulate population size. [27]

- Run Simulations: Execute the model for a burn-in period (without harvest) to reach demographic and genetic equilibrium. Then, introduce the harvest regime and run for the desired number of years.

Protocol 2: Estimating Effective Population Size (N_e) in an Age-Structured Population

This protocol uses the AgeNe method to calculate the effective population size from vital rates, which is crucial for understanding genetic drift in harvested populations. [30]

1. Construct a Life Table:

- Gather data or use model output for the following per-age-class (

x) vital rates:l_x: Cumulative survival from birth to agex.b_x: Mean number of offspring (recruits) produced by an individual of agex.s_x: Probability of survival from agextox+1.N_x: Number of individuals in age classx.φ_x: Ratio of the variance to the mean number of offspring produced by individuals of agex(requires individual reproductive success data).

2. Calculate Key Demographic Parameters:

- Generation Length (

T): The average age of parents of a newborn cohort. - Adult Population Size (

N): The total number of mature individuals. - Lifetime Variance in Reproductive Success (

V_k•): The variance in the total number of offspring produced by individuals over their lifetime.

3. Apply the AgeNe Formula:

- The effective population size per generation can be calculated as:

N_e = (N * T) / (1 + V_k•)This formula highlights thatN_eis reduced by a high variance in reproductive success. [30] - Interpretation: This calculated

N_ehelps assess the risk of loss of genetic diversity in the population due to genetic drift, which is critical for evaluating the long-term evolutionary impacts of harvest. [30]

Model Workflow and Relationships

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Modeling Components

This table details key "reagents," or conceptual components, essential for building models in this field.

| Research 'Reagent' | Function in the Model | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polygenic Trait Architecture | Models the genetic basis of complex, continuous traits (e.g., growth, maturation). [27] | The number of loci, allele effects, and degree of dominance determine heritability and evolutionary potential. |

| Von Bertalanffy Growth Parameters (L∞, k) | Describes individual growth trajectories over time. [30] | L∞ (asymptotic length) is often modeled as a heritable trait. k (growth rate) may be correlated with L∞. |

| Maturation Reaction Norm | Determines the probability of maturing at a given age and size, separating plastic and evolutionary responses. [27] | A key target of fishery-induced evolution; its genetic basis must be explicitly defined. |

| Genetic Relationship Matrix (GRM) | A matrix quantifying the genetic similarity between all individuals in a population based on markers. [31] | Used in Linear Mixed Models (LMMs) to account for relatedness and population structure in association studies. |

| Density-Dependent Function | Regulates population size by linking survival or growth to population density. [27] | Often applied to juvenile survival; critical for preventing unrealistic population explosions or crashes. |

| Harvest Mortality Rule | Defines the selective pressure of harvesting (e.g., size-based, gear-specific). [27] [30] | The specific rule (e.g., minimum-length limit) determines which phenotypes are selectively removed. |

| Effective Population Size (N_e) | Measures the size of an idealized population that would experience the same rate of genetic drift. [30] | N_e is often much smaller than the census size and is sensitive to life history and harvest. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Effective Population Size (Nâ‚‘) and why is it crucial for my research on harvested populations?

The effective population size (Nâ‚‘) is the size of an ideal population (one that meets all Hardy-Weinberg assumptions) that would lose heterozygosity (genetic variation) at a rate equal to that of your observed population [32]. In essence, it is the number of individuals in a population who contribute genetically to the next generation.

For research on harvested populations, Nâ‚‘ is a fundamental parameter because [32]:

- Genetic Drift: It quantifies the rate of genetic drift, which is the random change in allele frequencies from one generation to the next. Drift is stronger in smaller populations and can lead to the loss of genetic diversity.

- Sustainability: In harvested populations, a small Nâ‚‘ can signal increased vulnerability, as the loss of genetic diversity may reduce the population's ability to adapt to environmental changes or disease outbreaks.

- Model Accuracy: Using census population size (N) instead of Nâ‚‘ can lead to overestimates of a population's genetic health and long-term viability.

2. Why is my calculated Nâ‚‘ often much lower than the total census population size (N)?

It is common for Nâ‚‘ to be less than the total number of individuals counted (census size, N). Several factors can cause this discrepancy [32]:

- Fluctuating Population Size: Nâ‚‘ is heavily influenced by population bottlenecks. It is calculated as the harmonic mean of population sizes over time, which is disproportionately affected by the smallest population sizes in a series.

- Skewed Sex Ratios: An uneven ratio of breeding males to females reduces Nâ‚‘. For example, a population with many breeding females but only a few males will have a much lower Nâ‚‘ than its census size.

- Variance in Family Sizes: In an ideal population, the number of offspring per individual follows a Poisson distribution (mean equals variance). If the variance in offspring number is greater than the mean, Nâ‚‘ decreases. Conversely, if breeders are managed to have equal family sizes (zero variance), Nâ‚‘ can be larger than N.

- Overlapping Generations and Spatial Structure: These complex demographic factors can also act to reduce the effective size relative to the census count.

3. What is the difference between "variance effective size" and "inbreeding effective size"?

Both measure Nâ‚‘ but focus on different genetic consequences [32]:

- Inbreeding Effective Size focuses on changes in heterozygosity and the rate of inbreeding within a population from the parental generation's perspective.

- Variance Effective Size focuses on changes in genetic variance and the potential for interpopulation divergence from the offspring generation's perspective.

4. How do I calculate generation time for species with complex life histories?

Generation time (G) is the average age of parents of a newborn cohort. In a stable population, it can be calculated using the formula G = t / n, where 't' is the total time elapsed, and 'n' is the number of generations that occurred in that time [33] [34].

If you know the initial (Nâ‚€) and final (N) population sizes, you can first calculate the number of generations (n) and then the generation time [33]:

- Calculate the number of generations: n = (log(N) - log(Nâ‚€)) / log(2)

- Then calculate generation time: G = t / n

Table 1: Example Calculation of Generation Time for a Bacterial Culture

| Initial Population (Nâ‚€) | Final Population (N) | Time Elapsed (t, hours) | Number of Generations (n) | Generation Time (G, hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 8,000 | 6 | 3 | 2.0 |

| 500 | 4,000 | 8 | 3 | ~2.67 |

| 10,000 | 160,000 | 10 | 4 | 2.5 |

5. How are life-history trade-offs relevant to managing harvested populations?

Life-history theory examines how natural selection shapes traits like age at maturity, number of offspring, and lifespan to optimize reproductive success within ecological constraints [2]. These traits are subject to fundamental trade-offs, where an increase in one trait (e.g., current reproductive effort) leads to a decrease in another (e.g., future survival or growth) [2].

In harvested populations, understanding these trade-offs is critical because:

- Harvest as a Selective Pressure: Harvest often targets larger, older individuals, which can inadvertently select for life-history traits like earlier maturation or reduced size, potentially altering the population's demographic structure and productivity.

- Population Projections: Ignoring these evolutionary consequences can lead to inaccurate predictions about how a harvested population will respond over time. Management strategies should account for potential evolutionary changes driven by harvest pressure.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Calculating Nâ‚‘ and Generation Time

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Nâ‚‘ is drastically lower than N. | A past or present population bottleneck; a highly skewed breeding sex ratio [32]. | Review demographic history. If possible, calculate Nâ‚‘ using the harmonic mean of population sizes over several generations. Record and use the effective number of breeders. |

| Inconsistent Nâ‚‘ estimates from different genetic markers. | Different markers may reflect population history over different timescales or be influenced by selection. | Use multiple, neutral genetic markers. Apply several estimation methods (e.g., temporal method, linkage disequilibrium method) and compare results [32]. |

| Unable to calculate generation time directly. | Lack of data on individual birth and death rates; overlapping generations [2]. | For a stable population, use the Euler-Lotka equation from life-history theory, which incorporates age-specific survival and fecundity data to solve for generation time [2]. |

| Generation time calculation seems inaccurate for a slow-growing population. | The population may not be in a stable or growing state, violating model assumptions. | Ensure the population growth rate (r) is accurately estimated. For populations that are not stable, direct observation or genetic methods may be more appropriate. |

Essential Protocols

Protocol 1: Estimating Effective Population Size (Nâ‚‘) Using the Temporal Method

This method estimates Nâ‚‘ based on the change in allele frequencies over time [32].

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect genetic samples from the population at two or more time points (e.g., generations t and t+1).

- Genotyping: Genotype all individuals at several neutral, polymorphic genetic loci (e.g., microsatellites or SNPs).

- Allele Frequency Calculation: Calculate allele frequencies for each locus at each time point.

- Variance Estimation: Estimate the variance in allele frequency change (F) between time points.

- Nâ‚‘ Calculation: Apply the formula Nâ‚‘ = t / (2F), where 't' is the number of generations between samples, to estimate the variance effective size [32].

Protocol 2: Calculating Generation Time from Life-History Tables

This method provides a robust estimate of generation time using age-specific demographic data [2].

Methodology:

- Construct a Life Table: Gather data on age-specific survival (lâ‚“) and age-specific fecundity (mâ‚“).

- Calculate Net Reproductive Rate (R₀): R₀ = Σ(lₓmₓ). This is the average number of daughters produced by a female over her lifetime.

- Estimate Intrinsic Growth Rate (r): Solve the Euler-Lotka equation for r: 1 = Σe^(-rð‘¥)lâ‚“mâ‚“. This often requires iterative computation.

- Compute Generation Time (G): Once r is known, calculate generation time as G = ln(Râ‚€) / r.

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Population Genetic and Demographic Studies

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Neutral Genetic Markers (e.g., microsatellites, SNPs) | Used for genotyping individuals to estimate allele frequencies, genetic diversity, and relatedness for Nâ‚‘ calculations. They are assumed to not be under selection, providing a baseline for demographic inference. |

| Demographic Survey Equipment (e.g., GPS, camera traps, aerial drones) | Used to collect census data (N) and monitor population trends over time, which is critical for understanding population fluctuations that impact Nâ‚‘. |

Life-History Data Software (e.g., POPBIO, R packages like popdemo) |

Software tools used to construct life tables, analyze age-specific survival and fecundity, and apply the Euler-Lotka equation to calculate generation time. |

| Nâ‚‘ Estimation Software (e.g., NeEstimator, COLONY, TEMPOFS) | Specialized programs that implement various statistical methods (temporal, linkage disequilibrium, sibship assignment) for robust estimation of effective population size from genetic data [32]. |

Analyzing Probabilistic Maturation Reaction Norms (PMRNs)

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when designing experiments and analyzing Probabilistic Maturation Reaction Norms (PMRNs).

What is a PMRN and how does it help distinguish genetic change from plasticity?

A Probabilistic Maturation Reaction Norm (PMRN) is a statistical tool that describes an individual's probability of maturing as a function of its age and size, and potentially other traits like body condition [35] [36]. In the context of harvested populations, its primary strength is the potential to disentangle genetic changes in maturation schedules from phenotypically plastic responses to environmental variation [35] [36].

The core principle is that if the PMRN model fully accounts for the environmental influences on maturation (e.g., through its effects on growth), then any residual shift in the PMRN's position over time can suggest genetic change, often interpreted as fisheries-induced evolution [35] [37]. However, this interpretation is only valid if all major environmental drivers affecting maturation are included in the model [35].

My PMRN analysis shows a significant shift. Can I immediately conclude fisheries-induced evolution?

Not necessarily. A shift in the PMRN can indicate genetic change, but it can also result from unaccounted environmental factors [35] [38] [37].

A common issue is that the traditional two-dimensional PMRN (age and size) may not capture all phenotypic plasticity. For example, an experiment with zebrafish reared on different food levels found that plasticity in maturation was not entirely captured by age and size alone. Adding body condition as a third dimension accounted for more environmental variation, but significant differences between diet groups remained, indicating plasticity in the PMRN itself [35]. Similarly, a transplant experiment with white-spotted charr demonstrated that the PMRN for precocious males was plastic and varied with the stream environment [38].

- Recommendation: Always critically assess if other influential variables (e.g., condition, temperature, growth history) are missing from your model before concluding a genetic effect [35] [37].

Should I use a prospective or retrospective body size in my PMRN model?

The choice between prospective (body size at the beginning of the maturation interval) and retrospective (body size at the end of the interval) approaches can impact your results [37].

Evidence from a brown trout mark-recapture study suggests that in some systems, juvenile body size is a stronger predictor of maturation than annual growth [37]. However, the physiologically relevant trigger for maturation is often linked to the energy acquisition rate, which is more closely related to recent growth [37]. The "best" variable may be species- or population-specific.

- Troubleshooting: If possible, compare models using both size at the beginning (prospective) and size at the end (retrospective) of the interval to see which provides a better fit for your data [37].

How robust is the demographic method to violations of its assumptions?

The widely used demographic estimation method assumes that immature and mature individuals of the same age have equal growth and survival rates [35] [37]. In reality, these assumptions are often violated due to trade-offs associated with reproduction [37].

Simulation studies suggest the method can be robust with large sample sizes (>500), but biases can occur with smaller samples [37]. For instance, higher mortality in maturing fish can lead to an overestimation of the PMRN midpoint (the size and age at which maturation probability is 50%) [37].

- Solution: Whenever feasible, use mark-recapture data to directly observe the maturation transition, as this method does not rely on these assumptions [37]. If using the demographic method, be transparent about its limitations, especially with smaller datasets.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: PMRNs under Controlled Conditions

The following protocol is adapted from a laboratory experiment using zebrafish to assess the PMRN method, which provides a template for controlled studies [35].

Experimental Design and Organism

- Model Organism: Zebrafish (Danio rerio), third-generation offspring from a wild population to ensure a relatively similar genetic background [35].

- Key Factor Manipulation: Food availability. Fish were randomly assigned to one of five feeding levels: 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 4%, or 8% of dry food per aquarium biomass per day. This creates variation in growth and condition [35].

- Replication: Each diet treatment was replicated across five aquaria, with 50 fish per aquarium [35].

- Timing: The feeding experiment started at 85 days post-fertilization (dpf), once fish were large enough to withstand low-food treatments. Sampling occurred every 10-15 days thereafter [35].

Data Collection

- Sampling: At each sampling period, 25-50 fish were randomly selected from each diet group and culled [35].

- Core Measurements:

- Standard Length: Measured to the nearest mm.

- Wet Mass: Measured to the nearest 0.1 mg.

- Maturity Status: Determined via dissection and gonadal inspection. (Note: The original study used females only, as male maturity was hard to determine macroscopically) [35].

- Sex: Determined visually after dissection [35].

- Calculated Variable:

- Condition Factor: A surrogate for nutritional status. The relative condition factor (Kn) was calculated for each individual as:

Kn = W / Å´, whereWis the observed mass andÅ´is the predicted mass from the length-mass regression of the population [35].

- Condition Factor: A surrogate for nutritional status. The relative condition factor (Kn) was calculated for each individual as:

Data Analysis and PMRN Estimation

PMRNs were estimated using the demographic method, which involves three key steps [35] [39]:

- Estimate Maturity Ogives: Use a statistical model (e.g., logistic regression) to estimate the probability of being mature at a given combination of age and length (for a 2D PMRN) or age, length, and condition (for a 3D PMRN).

- Model Growth: Model the growth trajectory of the fish, for instance, using a von Bertalanffy or linear growth model.

- Calculate the PMRN: The probability of maturing is calculated from the maturity ogives and the growth model. The demographic method uses the formula:

P(maturing) = [P(mature|a+1, L+a) - P(mature|a,L)] / [1 - P(mature|a,L)], whereais age andLis length, accounting for growth [35] [39].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this experimental protocol:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for PMRN estimation under controlled conditions.

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from pivotal PMRN studies, highlighting the effects of environmental variables and methodological choices.