Comparative Analysis of Developmental Gene Regulatory Networks: From Evolutionary Insights to Therapeutic Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methods, applications, and challenges in the comparative analysis of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) across species, conditions, and developmental stages.

Comparative Analysis of Developmental Gene Regulatory Networks: From Evolutionary Insights to Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methods, applications, and challenges in the comparative analysis of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) across species, conditions, and developmental stages. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of GRN evolution, such as developmental system drift, and details cutting-edge computational methods for network reconstruction and comparison. The content further addresses key troubleshooting strategies for network analysis and validates approaches through case studies in evolution and disease modeling. By synthesizing insights from foundational, methodological, and applied perspectives, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging comparative GRN analysis to uncover core regulatory mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic targets for complex diseases.

The Principles and Evolution of Developmental Gene Regulatory Networks

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) are the fundamental conductors of development, orchestrating when and where genes turn on and off to shape an organism from a single cell to a complex adult. [1] This comparative analysis examines the core components and functional roles of GRNs, framing them as the central product in a landscape of diverse research methodologies. We will objectively compare the "performance" of different experimental and computational approaches used to map these networks, providing supporting data on their applications, outputs, and limitations.

Core Components of Gene Regulatory Networks

GRNs are intricate systems composed of interacting genes and regulatory elements. Their operation relies on a specific set of core components that work in concert to control gene expression with precision.

Transcription Factors (TFs): These proteins are the primary regulators within the network. They bind to specific DNA sequences to activate or repress the transcription of target genes. The combinatorial action of multiple TFs creates unique regulatory states that define specific cell types. [1]

Cis-Regulatory Elements: These are non-coding DNA sequences, including enhancers and silencers, that function as binding platforms for transcription factors. [1] Notably, super enhancers (SEs) are large clusters of enhancers that act as key regulatory hubs. They are characterized by extensive genomic span, dense enrichment of histone modifications (e.g., H3K27ac), and strong accumulation of coactivators and RNA polymerase II, which collectively drive high-level expression of genes critical for cell identity. [2]

Target Genes: These are the protein-coding or non-coding RNA genes whose expression is directly controlled by the transcription factors and cis-regulatory modules. Their products execute developmental programs, leading to processes like cell differentiation and morphogenesis. [1]

Non-Coding RNAs: This category includes microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), which play crucial post-transcriptional and epigenetic roles in fine-tuning gene expression. For instance, enhancer-derived RNAs (eRNAs) are a class of lncRNAs transcribed from enhancers that help stabilize chromatin looping and enhance promoter communication. [2] [3]

Table 1: Core Components of a Gene Regulatory Network

| Component | Functional Role | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | Master regulators that activate or repress gene transcription by binding to specific DNA sequences. | Execute combinatorial logic; define cell states; often form network hubs. |

| Cis-Regulatory Modules | DNA sequences (enhancers, silencers, promoters) that provide binding sites for transcription factors. | Integrate multiple regulatory inputs; determine the spatial and temporal pattern of gene expression. |

| Target Genes | Genes whose expression is controlled by the network, ultimately carrying out developmental functions. | Encode proteins for differentiation, proliferation, and morphogenesis. |

| Non-Coding RNAs | RNA molecules that regulate gene expression at the epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels. | Include miRNAs, lncRNAs, eRNAs; provide fine-tuning and stability to network outputs. |

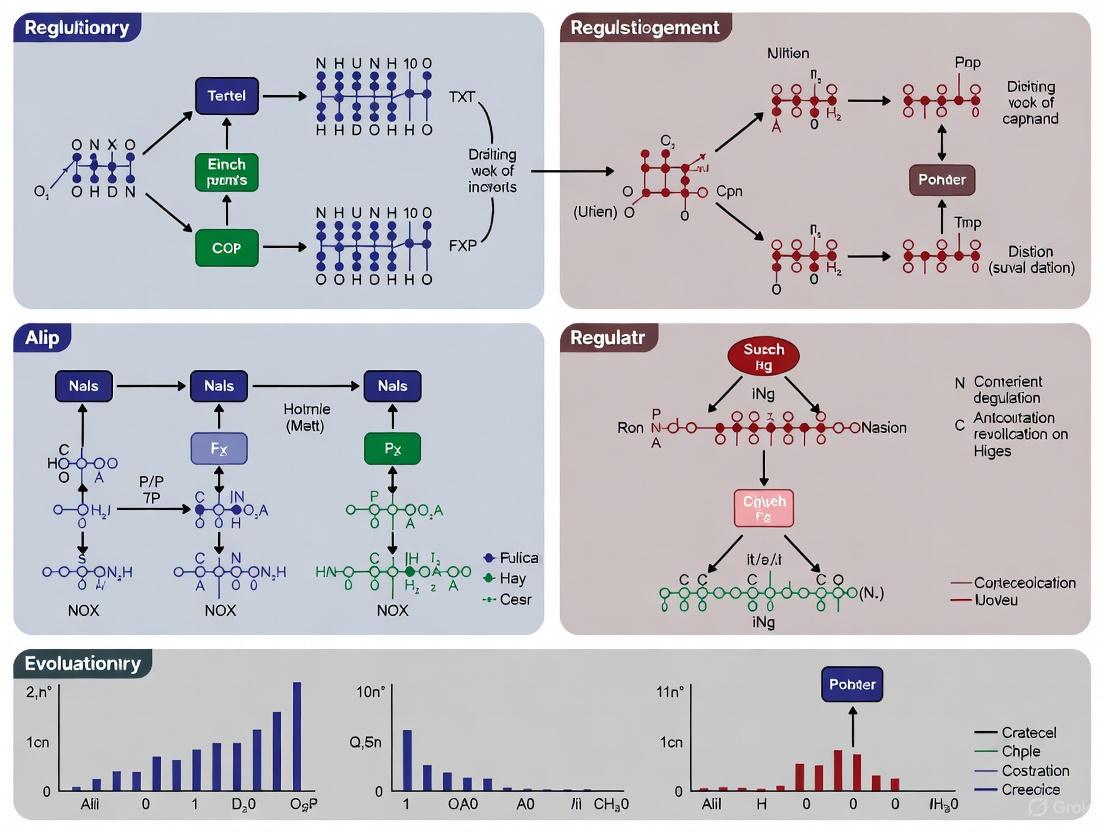

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and interactions between these core components in a basic GRN motif.

Functional Roles in Development: A Comparative Analysis of GRN Performance

The "performance" of a GRN can be evaluated by its ability to execute specific developmental tasks reliably. Different network architectures and regulatory strategies underpin key functions, from fate commitment to pattern formation. The table below compares the functional roles of various GRN types and components.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of GRN Functional Roles in Development

| Developmental Process | Key GRN Components & Properties | Functional Output & Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Fate Specification | Positive feedback loops; bistable systems; master transcription factors (e.g., NANOG, MyoD). | Irreversible commitment to a specific lineage. Metric: Precision of cell type generation. |

| Axis Formation & Patterning | Morphogen gradients; cross-regulatory interactions; mutual repression circuits. | Spatial organization of tissues and organs. Metric: Sharpness of boundary formation. |

| Temporal Regulation | Feed-forward loops; oscillatory networks (e.g., segmentation clock). | Precise timing of developmental events. Metric: Synchrony and periodicity of events. |

| Maintenance of Cellular Identity | Super enhancers; autoregulatory circuits; epigenetic modifications. | Stable gene expression programs over time. Metric: Resistance to transcriptional noise. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

To study these complex networks, researchers rely on a suite of powerful tools and reagents. The following table details essential materials used in modern GRN research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for GRN Analysis

| Research Reagent / Platform | Function in GRN Research |

|---|---|

| ChIP-seq | Identifies genome-wide binding sites for transcription factors and histone modifications (e.g., H3K27ac for active enhancers). [2] |

| ATAC-seq / DNase-seq | Probes chromatin accessibility, enabling the identification of active cis-regulatory elements, including super enhancers. [2] |

| Perturb-seq (CRISPR screens) | Uses CRISPR-based gene knockout coupled with single-cell RNA sequencing to unravel causal regulatory relationships and network topology. [4] [5] |

| Hi-C / ChIA-PET | Maps the 3D architecture of chromatin, revealing how enhancers and promoters physically interact via looping. [2] |

| RegNetwork Database | An open-source repository that curates known regulatory interactions between TFs, miRNAs, and genes in human and mouse, providing a prior knowledge base. [3] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | A class of AI models that process graph-structured data, used to predict molecular interactions and drug-target relationships in silico. [6] |

| PIM-35 | PIM-35, CAS:130445-55-5, MF:C10H12N2O, MW:176.21 g/mol |

| Nocardicin B | Nocardicin B|CAS 60134-71-6|Supplier |

Experimental Protocols for GRN Mapping

Understanding GRN function requires robust experimental methodologies. The following section details key protocols for mapping and validating network architecture and dynamics, providing a comparative view of their technical approaches.

Mapping Cis-Regulatory Architecture with ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq

This protocol identifies potential regulatory elements and their epigenetic states on a genome-wide scale.

- Step 1: Cell Fixation and Cross-linking. Treat cells with formaldehyde to cross-link DNA and associated proteins, preserving their in vivo interactions.

- Step 2: Chromatin Fragmentation. Use sonication or enzymatic digestion (e.g., with MNase) to shear cross-linked chromatin into small fragments.

- Step 3: Immunoprecipitation. For ChIP-seq, incubate chromatin with an antibody specific to a transcription factor (e.g., PU.1) or histone mark (e.g., H3K27ac). Capture the antibody-bound complexes. For ATAC-seq, skip to Step 4.

- Step 4: Library Preparation and Sequencing. Reverse cross-links, purify DNA, and prepare a sequencing library from the immunoprecipitated DNA (ChIP-seq) or from DNA accessed by the Tn5 transposase (ATAC-seq).

- Step 5: Data Analysis. Map sequencing reads to a reference genome. Call peaks to identify enriched regions, which represent transcription factor binding sites or open chromatin regions. SEs can be identified from ChIP-seq data by stitching together typical enhancers in close genomic proximity that are highly enriched for mediator complex proteins like MED1. [2]

The workflow for this integrated approach is visualized below.

Inferring Causal Relationships with Perturb-seq

This high-resolution protocol moves beyond correlation to establish causality within GRNs by combining genetic perturbation with single-cell transcriptomics.

- Step 1: Design and Clone sgRNAs. Design single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting genes of interest (e.g., transcription factors) and clone them into a lentiviral vector containing a cell barcode.

- Step 2: Generate Perturbed Cell Population. Transduce a pool of cells (e.g., K562 cells) with the sgRNA library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA.

- Step 3: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. After a period for gene expression changes to occur, partition the perturbed cells into droplets for single-cell RNA-seq (e.g., using the 10x Genomics platform). This captures the transcriptome of each cell and the barcode of the sgRNA it contains.

- Step 4: Causal Network Inference. Bioinformatically align cells by their perturbation. Compare expression changes in target genes across cells with different perturbations to reconstruct causal regulatory relationships. A study applying this method in K562 cells found that only 41% of gene perturbations had a measurable effect on transcription, highlighting network robustness, and identified a network with small-world and scale-free properties. [4] [5]

Comparative Analysis of Computational GRN Inference Methods

Beyond wet-lab experiments, computational approaches are indispensable for GRN inference. The table below compares the performance of different methodological classes.

Table 4: Comparison of Computational GRN Inference Methods

| Methodology | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-expression Networks | Infers associations based on gene expression correlation across samples. | Simple to implement; useful for hypothesis generation. | Identifies correlative, not causal, relationships; high false-positive rate. |

| Linear Models on DAGs | Models gene expression as a linear function of its regulators on a Directed Acyclic Graph. | Computationally efficient; well-established statistical framework. | Poorly captures feedback loops and non-linear regulatory logic. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Uses deep learning on graph structures to learn complex regulatory rules from molecular data. | Directly models graph data; can integrate multi-modal data; high predictive accuracy. | "Black box" nature limits interpretability; requires large amounts of labeled data and computing resources. [6] |

| Perturbation-based Causal Inference | Leverages interventional data (e.g., from Perturb-seq) to infer causal directionality. | Directly infers causal relationships; high biological relevance. | Experimentally costly and complex; scaling to whole genome remains challenging. [4] |

Gene regulatory networks perform as highly robust and modular systems to direct development. Their performance in ensuring precise cell fate decisions, spatial patterning, and temporal control is dictated by core architectural principles, including their scale-free topology, hierarchical organization, and specific motifs like feedback loops. A comparative analysis of research methods reveals that no single approach is sufficient; rather, a synergistic combination of high-resolution epigenetic mapping, causal perturbation studies, and increasingly sophisticated computational models like Graph Neural Networks is required to fully elucidate the structure and function of these networks. This integrated understanding is pivotal not only for deciphering normal development but also for unraveling the etiologies of developmental disorders and congenital diseases.

The intricate architecture of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) serves as the fundamental engine driving embryonic development, controlling processes such as cell differentiation, body patterning, and morphogenesis [7]. The comparative analysis of these networks across species reveals the dynamic interplay between conservation and divergence that shapes evolutionary trajectories. While the core developmental genes and their expression patterns often remain remarkably conserved, the underlying regulatory sequences and network interactions can diverge significantly through a process known as Developmental System Drift (DSD) [8]. This phenomenon, whereby homologous characters across taxa are formed by divergent developmental processes, illustrates the remarkable plasticity of developmental systems in their response to natural selection. Understanding these evolutionary dynamics requires integrating comparative genomics with sophisticated computational modeling to reconstruct network architectures and their evolutionary histories.

Advanced computational methods now enable researchers to move beyond simple sequence comparisons to identify regulatory element conservation even in the absence of sequence similarity [9]. Simultaneously, novel reverse-engineering approaches allow the inference of GRN architecture from gene expression data, revealing how network topology and dynamics evolve [10] [11]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the experimental and computational methodologies driving these discoveries, offering researchers a framework for investigating the evolutionary dynamics of developmental systems.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Element Conservation

Sequence-Based versus Positional Conservation of Cis-Regulatory Elements

The conservation of cis-regulatory elements (CREs) presents a paradox in evolutionary developmental biology. While developmental gene expression patterns are deeply conserved across vast evolutionary distances, the CRE sequences that control these patterns often show remarkable divergence [9]. Traditional alignment-based methods like LiftOver identify only a fraction of functionally conserved regulatory elements—approximately 10% of enhancers and 22% of promoters between mouse and chicken [9]. This limitation stems from the rapid turnover of noncoding sequences that confounds direct sequence alignment, especially at larger evolutionary distances.

Synteny-based algorithms such as Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) have dramatically improved our ability to detect conserved regulatory elements by leveraging genomic position rather than sequence similarity [9]. This approach identifies "indirectly conserved" elements that maintain their positional context within genomic regulatory blocks despite sequence divergence. Through bridged alignments using multiple species, IPP increases the detection of conserved promoters more than threefold (from 18.9% to 65%) and enhancers more than fivefold (from 7.4% to 42%) in mouse-chicken comparisons [9].

Table 1: Conservation of Regulatory Elements Between Mouse and Chicken Embryonic Hearts

| Element Type | Sequence-Conserved (LiftOver) | Positionally Conserved (IPP) | Fold Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoters | 22% | 65% | 3.4x |

| Enhancers | 10% | 42% | 5.7x |

Functional Validation of Diverged Regulatory Elements

The functional significance of sequence-diverged CREs has been demonstrated through in vivo enhancer-reporter assays [9]. These experiments reveal that positionally conserved enhancers with highly diverged sequences can drive similar expression patterns in cross-species transgenic models. For example, chicken enhancers with minimal sequence conservation can successfully recapitulate expected expression patterns in mouse embryos, confirming their functional conservation despite millions of years of evolutionary divergence.

Notably, these indirectly conserved elements exhibit similar chromatin signatures and sequence composition to sequence-conserved CREs, but show greater shuffling of transcription factor binding sites between orthologs [9]. This binding site rearrangement explains why traditional alignment methods fail to detect them while maintaining their core regulatory function through preserved three-dimensional chromatin architecture and relative positioning within topologically associating domains (TADs).

Methodologies for Gene Regulatory Network Reconstruction

Reverse-Engineering Developmental GRNs from Spatial Expression Data

The gene circuit method represents a powerful approach for reverse-engineering developmental GRNs from quantitative spatial gene expression data [10]. This method uses mathematical models called gene circuits that represent the embryo as a row of nuclei, each containing an identical regulatory network. The model incorporates three key processes: (1) regulated gene product synthesis, (2) gene product diffusion, and (3) linear gene product decay [10]. Regulatory interactions are represented through a genetic interconnectivity matrix, where weights indicate activation, repression, or no interaction.

Table 2: Comparison of GRN Reverse-Engineering Methodologies

| Method | Data Requirements | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Circuit Method [10] | Quantitative spatial expression patterns from in situ hybridization or immunofluorescence | Differential equation models incorporating diffusion; Global optimization of parameters | Gap gene network in Drosophila blastoderm; Pattern-forming networks | Experimentally intensive data acquisition; Computationally challenging |

| GRLGRN [12] | scRNA-seq data; Prior GRN knowledge | Graph transformer networks; Attention mechanisms; Contrastive learning | Cellular dynamics; Heterogeneous cell populations | Dependent on quality of prior network; Requires substantial computational resources |

| MCMC Topology Search [13] | Target expression patterns; Morphogen gradient specifications | Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling of network space; Multi-input processing | Identification of pattern-forming motifs; Synthetic biology design | Limited to small networks (3-node); In silico validation only |

Successful application of the gene circuit method to the Drosophila gap gene network demonstrated that reverse-engineering is possible with reduced experimental effort when focusing on key features like expression domain boundaries rather than precise expression levels [10]. This network, comprising hunchback, Krüppel, giant, and knirps, is regulated by maternal gradients of Bicoid, Hunchback, and Caudal, and repressive inputs from Tailless and Huckebein [10]. The minimal data requirements for successful inference include accurate measurement of timing and position of expression domain boundaries, which contain crucial regulatory information for determining network structure.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing and Deep Learning Approaches

Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing have enabled the development of sophisticated deep learning models for GRN inference from heterogeneous cell populations. The GRLGRN framework uses graph transformer networks to extract implicit regulatory relationships from prior GRN knowledge and single-cell gene expression profiles [12]. This approach incorporates attention mechanisms to improve feature extraction and graph contrastive learning to prevent over-smoothing of gene features.

GRLGRN has demonstrated superior performance compared to previous methods, achieving an average improvement of 7.3% in AUROC and 30.7% in AUPRC across seven cell-line datasets with three different ground-truth networks [12]. The model excels at identifying hub genes and uncovering implicit links in the regulatory architecture, providing both predictive accuracy and interpretability for network dynamics in diverse cellular contexts.

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Reverse-Engineering GRNs Using the Gene Circuit Method

Application: Reconstructing the topology and dynamics of pattern-forming gene regulatory networks from spatial expression data [10].

Workflow:

- Sample Collection and Fixation: Collect Drosophila embryos at blastoderm stage (nuclear cycle 14A) and fix in formaldehyde-based fixative.

- Spatial Expression Visualization: Perform whole-mount in situ hybridization for target gap genes (hb, Kr, gt, kni) using fluorescently labeled probes. Alternatively, use immunofluorescence with antibody staining for gap protein detection.

- Image Acquisition: Capture high-resolution images of stained embryos using confocal laser-scanning microscopy with consistent settings across samples.

- Image Processing and Data Quantification:

- Segment images to identify individual nuclei

- Classify embryos by temporal class using morphological markers

- Remove non-specific background staining

- Register data to minimize embryo-to-embryo variability

- Integrate expression data into consistent spatial coordinates along the antero-posterior axis

- Gene Circuit Optimization:

- Initialize gene circuit model with random regulatory parameters

- Implement global optimization algorithm (e.g., parallel Lam Simulated Annealing)

- Iteratively adjust parameters to minimize difference between model output and expression data

- Continue optimization until no significant improvement in fit is achieved

- Network Analysis: Extract regulatory matrix from best-fitting models and analyze network topology and dynamics.

Protocol: Identifying Conservation of Diverged Regulatory Elements

Application: Detection of functionally conserved regulatory elements with highly diverged sequences across evolutionary distances [9].

Workflow:

- Tissue Collection: Dissect embryonic hearts from mouse (E10.5-E11.5) and chicken (HH22-HH24) at equivalent developmental stages.

- Chromatin Profiling:

- Perform ATAC-seq to map chromatin accessibility

- Conduct ChIPmentation for H3K27ac and H3K4me3 histone modifications

- Implement Hi-C to capture 3D chromatin architecture

- Extract RNA for transcriptome analysis (RNA-seq)

- CRE Identification: Use CRUP software or similar tools to predict enhancers and promoters from integrated chromatin data.

- Synteny-Based Orthology Mapping:

- Apply Interspecies Point Projection algorithm with multiple bridging species

- Classify projections as directly conserved, indirectly conserved, or non-conserved

- Validate orthology through shared chromatin features and genomic context

- Functional Validation:

- Clone candidate enhancers into reporter vectors (e.g., lacZ or GFP)

- Inject constructs into fertilized mouse oocytes

- Analyze expression patterns in transgenic embryos

- Compare patterns with endogenous gene expression

Network Topology and Evolutionary Dynamics

Modularity and Evolvability in Developmental GRNs

Developmental GRNs exhibit functional modularity that enables specific aspects of network behavior to evolve independently. Analysis of the dipteran gap gene network reveals that although the network lacks structural modularity, it comprises dynamical modules that drive distinct features of the expression pattern [11]. These subcircuits share the same regulatory structure but differ in their components and sensitivity to regulatory interactions, with some operating in a state of criticality while others do not.

This organization has profound implications for evolvability. The gap gene system shows differential evolvability of various expression features, with some aspects of the pattern being more constrained than others [11]. This variation in evolutionary flexibility correlates with the criticality of the underlying dynamical modules, suggesting that networks evolve through changes in both topology and the dynamical regime of their constituent modules.

Network Motifs and Their Evolutionary Implications

GRNs contain overrepresented network motifs—recurring topological patterns that perform specific regulatory functions. The most abundant three-node motif is the incoherent feed-forward loop (I-FFL), which can generate diverse dynamical behaviors including pulse generation, acceleration of responses, and fold-change detection [13] [7]. Computational searches of network space have identified 714 classes of three-node network topologies capable of generating striped expression patterns in response to morphogen gradients, with I-FFLs representing the predominant solution [13].

The enrichment of specific motifs in GRNs may result from either convergent evolution for optimal regulatory performance or as a non-adaptive byproduct of network growth mechanisms [7]. Support for the adaptive hypothesis comes from observations that specific motifs are associated with precise dynamical functions like noise suppression or response acceleration. However, simulations show that random network generation can also produce motif enrichment under certain conditions, complicating evolutionary interpretations.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Evolutionary GRN Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Profiling | ATAC-seq; ChIPmentation; Hi-C; RNA-seq | Mapping chromatin accessibility, histone modifications, 3D architecture, and gene expression | Genome-wide coverage; Single-cell compatibility; High resolution |

| Spatial Expression Analysis | Whole-mount in situ hybridization; Immunofluorescence; Confocal microscopy | Quantifying gene expression patterns in embryonic contexts | Cellular resolution; Multiplexing capability; Quantitative output |

| Transgenic Validation | LacZ/GFP reporter constructs; Mouse transgenesis; CRISPR/Cas9 | Testing enhancer function in vivo; Genetic perturbation | Functional validation; Cross-species compatibility; Precise editing |

| Sequence Alignment | LiftOver; Blastz; TBA; ClustalW; Mavid | Identifying sequence-conserved regions; Multiple genome alignments | Standardized pipelines; Parameter optimization; Batch processing |

| Synteny Analysis | Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) | Detecting positionally conserved regulatory elements | Bridged alignments; Multiple species integration; Positional interpolation |

| GRN Inference | Gene Circuit Method; GRLGRN; GENIE3; GRNBoost2 | Reconstructing regulatory networks from expression data | Spatial modeling; Deep learning; Prior knowledge integration |

| Motif Analysis | CisEvolver; MCMC topology search | Simulating binding site evolution; Exploring network design space | Evolutionary modeling; Binding site simulation; Pattern generation |

| Aureusidin | Aureusidin|Natural Aurone for Research|RUO | High-purity Aureusidin, a natural aurone flavonoid. Explore its research applications in inflammation, gout, and metabolism. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Valsartan | Valsartan | High-purity Valsartan for research. Explore its role as an ARB in hypertension and cardiovascular studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Gene Regulatory Network Inference from Single-Cell Data

Diagram Title: GRLGRN Inference Workflow from Single-Cell Data

Evolutionary Conservation of Regulatory Elements

Diagram Title: Regulatory Element Conservation Pipeline

The process of gastrulation, while morphologically conserved across the animal kingdom, is controlled by diverse cellular mechanisms. This raises a fundamental question in evolutionary developmental biology: to what extent do conserved gene regulatory networks (GRNs) underlie this critical developmental process in phylogenetically distant species? Research on developmental system drift reveals that even when the morphological outcome remains constant, the underlying genetic programs can diverge significantly over evolutionary time [14]. This phenomenon is particularly well-illustrated in corals of the genus Acropora, which have become a model system for studying the evolution of developmental GRNs.

Comparative studies of GRN architecture provide crucial insights into how developmental processes evolve while maintaining functional outcomes. The concept of developmental system drift suggests that different genetic pathways can achieve the same morphological result through compensatory changes throughout the network [14]. Studying these patterns in corals offers a unique perspective on the evolutionary flexibility of developmental programs and the identification of core regulatory elements that remain stable over millions of years of evolution.

Comparative GRN Analysis in Acropora Species

Experimental Design and Genomic Comparisons

A systematic comparison of gene expression profiles during gastrulation was conducted using two coral species: Acropora digitifera and Acropora tenuis. These species diverged approximately 50 million years ago, providing sufficient evolutionary time for genetic changes to accumulate while maintaining morphological similarity during gastrulation [14]. Researchers employed comprehensive transcriptomic analyses to characterize temporal gene expression patterns throughout this critical developmental window.

The experimental approach involved:

- High-throughput sequencing to capture transcriptomes at multiple developmental stages

- Comparative orthology mapping to identify corresponding genes between species

- Temporal expression profiling to track gene activation patterns during gastrulation

- Modular network analysis to identify co-regulated gene sets and their conservation

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Acropora Study System

| Feature | Acropora digitifera | Acropora tenuis |

|---|---|---|

| Divergence Time | ~50 million years | ~50 million years |

| Morphological Outcome | Conserved gastrulation | Conserved gastrulation |

| GRN Architecture | Significant divergence | Significant divergence |

| Paralog Usage | Greater divergence, neofunctionalization | More redundant expression |

| Alternative Splicing | Species-specific patterns | Species-specific patterns |

Key Findings: Divergence and Conservation

The comparative analysis revealed substantial regulatory network diversification between the two Acropora species. Orthologous genes showed significant temporal and modular expression divergence, indicating extensive rewiring of the GRN controlling gastrulation [14]. Despite this overall divergence, researchers identified a core set of 370 differentially expressed genes that were consistently up-regulated at the gastrula stage in both species [14].

This conserved regulatory "kernel" contained genes with known roles in:

- Axis specification and embryonic patterning

- Endoderm formation and germ layer specification

- Neurogenesis and neural differentiation

The persistence of this kernel despite extensive peripheral rewiring suggests these genes constitute an essential, constrained core of the gastrulation program. Beyond this kernel, the species exhibited notable differences in paralog usage and alternative splicing patterns, indicating independent evolutionary trajectories in regulatory network architecture [14].

Table 2: Conserved and Divergent Features in Acropora Gastrulation GRNs

| Feature | Conserved Elements | Divergent Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Kernel | 370 gastrula-upregulated genes | Peripheral network connections |

| Biological Processes | Axis specification, endoderm formation, neurogenesis | Timing of gene expression, module connectivity |

| Genetic Mechanisms | Core transcription factors | Paralogue usage, alternative splicing patterns |

| Network Properties | Essential regulatory logic | Regulatory robustness and redundancy |

Methodology: Experimental Protocols for GRN Analysis

Transcriptomic Profiling and Network Reconstruction

The experimental workflow for GRN analysis in Acropora species involved multiple complementary approaches to ensure comprehensive network mapping:

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Embryos were collected at precisely timed developmental stages spanning early gastrulation through late gastrulation

- Biological replicates were maintained for statistical robustness (typically n≥3 per stage)

- Samples were immediately stabilized using RNA preservation reagents to maintain expression profiles

RNA Sequencing and Data Processing:

- Total RNA was extracted using column-based purification methods

- Library preparation employed stranded mRNA-seq protocols to maintain directional information

- High-throughput sequencing was performed on Illumina platforms with sufficient depth (typically ≥30 million reads per sample)

- Quality control was implemented using FastQC [14] to ensure data reliability

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Read alignment to respective reference genomes (A. digitifera and A. tenuis)

- Transcript abundance quantification using expectation-maximization algorithms

- Differential expression analysis employing statistical frameworks (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR)

- Orthology mapping using reciprocal best BLAST hits and synteny information

Network Inference and Comparative Analysis

GRN Reconstruction:

- Co-expression networks were built using weighted correlation methods

- Regulatory interactions were inferred using Bayesian network approaches

- Cis-regulatory element analysis complemented expression-based inferences

Comparative Framework:

- Orthologous genes were mapped between species

- Expression trajectories were compared across developmental time

- Modular structure was analyzed using community detection algorithms

- Conservation scores were calculated for network edges and nodes

Regulatory Network Architecture: Kernels and Peripheral Circuits

Conserved Kernel Structure and Function

The regulatory kernel identified in the Acropora study represents a network subcircuit that remains stable despite extensive evolutionary divergence in surrounding networks. This kernel consists of interconnected genes that maintain conserved expression patterns and regulatory relationships. In developmental biology, such kernels are theorized to underlie the stability of essential developmental processes across evolutionary timescales.

The 370-gene kernel showed functional enrichment for fundamental developmental processes:

- Transcription factors with homeodomain and bHLH motifs

- Signaling pathway components including Wnt and TGF-β receptors

- Cell adhesion molecules critical for morphogenetic movements

- Cytoskeletal regulators involved in cell shape changes

The preservation of this kernel despite approximately 50 million years of divergence highlights the evolutionary constraint on core developmental processes. This finding aligns with the concept of "kernels" in GRN theory – subcircuits that are resistant to evolutionary change due to their essential developmental functions and interconnected nature [14].

Mechanisms of Network Diversification

Beyond the conserved kernel, the Acropora GRNs exhibited significant divergence through multiple genetic mechanisms:

Paralog Divergence and Neofunctionalization:

- A. digitifera showed greater paralog divergence, consistent with neofunctionalization

- A. tenuis exhibited more redundant expression patterns between paralogs

- Differential paralog usage contributed to regulatory network rewiring

Alternative Splicing Variation:

- Species-specific alternative splicing patterns were identified

- Differential isoform usage affected protein interaction domains

- Splicing changes altered regulatory connections in peripheral circuits

Cis-Regulatory Evolution:

- Non-coding regions showed accelerated divergence rates

- Transcription factor binding site turnover altered regulatory connections

- Compensatory mutations maintained output despite input changes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for GRN Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in GRN Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Platforms | BioTapestry [15] [16], Cytoscape [15] [17] | GRN visualization, modeling, and comparative analysis |

| Sequence Analysis Tools | FastQC [14], Orthology mapping algorithms | Data quality control, cross-species gene correspondence |

| Experimental Validation Systems | Cis-regulatory analysis, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing | Functional testing of regulatory predictions |

| Database Resources | Molecular interaction databases, Expression atlases | Context for network interpretation and validation |

| H-Lys-lys-pro-tyr-ile-leu-OH | H-Lys-Lys-Pro-Tyr-Ile-Leu-OH Research Peptide | H-Lys-Lys-Pro-Tyr-Ile-Leu-OH is a synthetic peptide for neurotensin receptor (NTS1) research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| O-Coumaric Acid | O-Coumaric Acid, CAS:614-60-8, MF:C9H8O3, MW:164.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The BioTapestry platform deserves particular emphasis for GRN studies. This open-source, specialized tool addresses the unique challenges of GRN representation through several key features [16]:

- Hierarchical network views showing different temporal and spatial contexts

- Cis-regulatory focus with explicit representation of regulatory DNA

- Bundled link drawing to reduce visual complexity in large networks

- Annotation capabilities for documenting experimental evidence

For comparative studies across species, BioTapestry supports the organization of network variants while maintaining connection to the core architecture, making it particularly valuable for evolutionary developmental biology research [16].

Comparative Framework: Insights from Echinoderm Models

Parallels with Echinoderm GRN Evolution

Research in echinoderms (sea urchins, sea stars) provides a valuable comparative framework for understanding GRN evolution in corals. The sea urchin endomesoderm specification GRN represents one of the most comprehensively mapped developmental networks, enabling detailed evolutionary comparisons [18] [19].

A systematic comparison of sea urchin and sea star GRNs revealed how novelty incorporation occurs while maintaining network stability [19]. Key findings include:

- Network motifs with positive feedback tend to be highly conserved

- Cis-regulatory modules with specific transcription factor binding site arrangements constrain evolution

- Co-option mechanisms allow redeployment of existing subcircuits for new functions

The development of the sea urchin larval skeleton, an evolutionary novelty, illustrates how new cell types can arise through network rewiring while preserving essential functions [18]. This parallel with Acropora findings suggests general principles for GRN evolution across phylogenetically distant taxa.

Signaling Mode Switches in GRN Evolution

The echinoderm research revealed a crucial mechanism for GRN evolution: signaling mode switches. In sea stars, Delta and HesC are co-expressed and engage in lateral inhibition, while in sea urchins, the incorporation of Pmar1 creates spatial separation leading to inductive signaling [19]. This demonstrates how network changes can switch signaling between different modes (lateral inhibition vs. induction) while maintaining functional outcomes.

This concept extends to the Acropora findings, where conserved kernels may maintain essential functions despite changes in signaling modes or regulatory connections in peripheral circuits. The stability of developmental processes thus depends on hierarchical network organization with constrained core elements and flexible peripheral components.

The study of gastrulation in Acropora corals provides fundamental insights into the principles governing GRN evolution. The identification of a conserved regulatory kernel amidst extensive network diversification demonstrates the hierarchical nature of evolutionary constraint in developmental systems. These findings align with and extend principles observed in echinoderm models, suggesting general mechanisms for balancing developmental stability and evolutionary flexibility.

The concept of developmental system drift exemplified by the Acropora system has broad implications for understanding how complex traits evolve while maintaining functional outcomes. The recognition that different genetic architectures can achieve conserved morphological results challenges simple genotype-phenotype mapping and highlights the importance of network-level analysis in evolutionary biology.

Future research directions emerging from this work include:

- Functional validation of kernel components through genetic manipulation

- Extension to other taxa to determine kernel conservation across greater evolutionary distances

- Integration with epigenomics to understand regulatory constraint mechanisms

- Application to disease models where network rewiring may underlie pathological states

The comparative GRN framework established through Acropora and echinoderm research provides a powerful approach for deciphering the evolutionary dynamics of developmental systems and identifying the core principles that govern the evolution of biological complexity.

The Impact of Gene Duplication and Alternative Splicing on GRN Diversification

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) are collections of molecular regulators that interact to govern gene expression levels, determining cellular function and playing a central role in morphogenesis and evolutionary developmental biology [7]. The evolution of complexity in multicellular organisms has been driven by mechanisms that expand proteomic diversity, with gene duplication (GD) and alternative splicing (AS) representing two fundamental evolutionary processes for generating functional variation [20] [21]. Gene duplication provides raw genetic material for innovation by creating paralogous genes, while alternative splicing enables single genes to produce multiple transcript isoforms through differential exon inclusion [22]. Understanding how these two mechanisms interact to shape GRN diversification is essential for unraveling the evolutionary origins of cellular specialization and organismal complexity. This comparative analysis examines their respective contributions, evolutionary relationships, and combined impact on the specialization of gene regulatory networks across diverse taxa.

Quantitative Comparison of Duplication and Splicing Patterns

Genomic Scale Trends and Evolutionary Dynamics

Large-scale comparative genomic analyses reveal complex relationships between gene duplication and alternative splicing across the tree of life. A study of 1,494 species established that alternative splicing is highly variable across lineages, with mammals and birds exhibiting the highest levels, while unicellular eukaryotes and prokaryotes show minimal splicing activity [22]. The same research proposed a novel genome-scale metric, the Alternative Splicing Ratio (ASR), which quantifies the average number of distinct transcripts generated per coding sequence, enabling standardized cross-species comparisons.

Table 1: Evolutionary Comparison of Gene Duplication and Alternative Splicing

| Characteristic | Gene Duplication (GD) | Alternative Splicing (AS) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | DNA- or RNA-based duplication of genetic loci [21] | Post-transcriptional processing of pre-mRNA [22] |

| Evolutionary Rate | One new splice form per gene every 385 million years [23] | Rapid evolution via splice site mutations [21] |

| Impact on Protein Sequence | Generally more conservative changes [24] | Often more drastic protein sequence/structure changes [24] |

| Relationship to Organismal Complexity | Positive correlation with proteome size [21] | Strong correlation with number of cell types [21] [22] |

| Temporal Pattern | Immediate creation of genetic redundancy [21] | Age-dependent gain of splice forms [23] |

The relationship between GD and AS demonstrates significant temporal dependency. Research shows that genes progressively gain new splice variants with time, with duplicates acquiring splice forms at an estimated rate of 2.6 × 10^(-3) new splice forms per gene per million years [23]. This age-dependent pattern explains apparent contradictions in earlier studies, as recently duplicated genes show lower AS levels while ancient duplicates exhibit higher AS propensity than singletons [23] [25].

Gene Family Size and Alternative Splicing Propensity

The relationship between gene duplication and alternative splicing varies considerably with gene family size and evolutionary age. Analyses stratified by duplication age reveal that ancient duplicated genes display higher alternative splicing proportions and more splice isoforms compared to both recent duplicates and singletons [25].

Table 2: Alternative Splicing Patterns by Gene Family Size in Human Genes

| Gene Family Size | AS Proportion (Recent Duplicates) | AS Proportion (Ancient Duplicates) | Average AS Isoforms (Ancient Duplicates) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singletons (1) | 65% [25] | 65% [25] | ~3.2 [25] |

| Small (2-4) | <49% [25] | >67% [25] | ~3.8 [25] |

| Moderate (5-7) | ~50% [25] | >68% [25] | ~4.2 [25] |

| Large (≥8) | <48% [25] | <60% [25] | ~2.9 [25] |

This data demonstrates a clear pattern: for slightly or moderately duplicated genes (family size 2-7), genes are more likely to evolve alternative splicing and have a greater number of AS isoforms after long-term evolution compared to singleton genes [25]. In contrast, large gene families (≥8 members) maintain lower AS proportions across evolutionary timescales, suggesting distinct evolutionary constraints operating on highly duplicated gene families [25] [26].

Evolutionary Models of Interaction Between Duplication and Splicing

Theoretical Frameworks for Relationship Dynamics

Three primary evolutionary models have been proposed to explain the relationship between gene duplication and alternative splicing, each with distinct mechanistic and functional implications [21]:

The Independent Model posits no functional relationship between GD and AS, predicting similar isoform numbers in paralogs and non-duplicated genes [21]. The Functional Sharing Model illustrates subfunctionalization, where paralogs partition ancestral AS events between them, decreasing AS per gene [21]. The Accelerated AS Model predicts increased AS events per gene due to relaxed selective pressure on each paralog [21]. Empirical evidence suggests that the predominant evolutionary outcome is expression specialization, mostly coupled with functional specialization, for both paralogous genes and alternative isoforms throughout animal evolution [27].

Molecular Mechanisms of Splicing Divergence in Duplicates

At the molecular level, the divergence of alternative splicing patterns after gene duplication occurs through specific mutational mechanisms affecting regulatory elements. Research has demonstrated that exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) and exonic splicing silencers (ESSs) diverge especially fast shortly after gene duplication [28].

Table 3: Experimental Protocol for Analyzing Splicing Element Divergence

| Methodological Step | Technical Approach | Key Parameters Measured |

|---|---|---|

| Identification of Paralogs | Sequence similarity clustering (e.g., CD-HIT) [25] | Synonymous substitution rate (Ks) as proxy for duplication age [28] |

| Splicing Element Detection | RESCUE-ESE method, octamer frequency analysis [28] | ESE/ESS densities, motif conservation |

| Divergence Quantification | Binomial distribution testing for asymmetric evolution [28] | Proportion of paralogous exons with significant ESE/ESS differences |

| Functional Validation | Splicing state transition analysis [28] | Exon constitutive/alternative splicing status |

Approximately 10% and 5% of paralogous exons undergo significantly asymmetric evolution of ESEs and ESSs, respectively [28]. These changes are primarily caused by synonymous mutations, though nonsynonymous changes also contribute, and result in exon splicing state transitions (from constitutive to alternative or vice versa) [28]. The proportion of paralogous exon pairs with different splicing states increases over evolutionary time, confirming that ESE and ESS changes after gene duplication significantly contribute to the generation of new gene structures [28].

This molecular pathway illustrates how sequence divergence after duplication directly affects splicing regulatory elements, leading to the acquisition of distinct alternative splicing profiles in paralogs, ultimately contributing to GRN diversification through expanded regulatory capacity and tissue-specific expression patterns.

Experimental Approaches for Analyzing Duplication-Splicing Interactions

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Investigating the interplay between gene duplication and alternative splicing requires integrated genomic, transcriptomic, and evolutionary analyses. Standardized protocols have emerged for quantifying relationships and detecting signatures of evolutionary selection.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Duplication-Splicing Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| NCBI Annotation Files | Standardized gene models for cross-species ASR calculation [22] | Alternative Splicing Ratio computation [22] |

| CD-HIT Cluster Suite | Sequence similarity clustering for paralog identification [25] | Gene family size classification at different identity thresholds [25] |

| RESCUE-ESE Algorithm | Computational identification of exonic splicing enhancers [28] | ESE density comparison between paralogous exons [28] |

| EST/cDNA Libraries | Experimental evidence for splice variant identification [23] | Isoform validation and quantification [23] |

| Ensembl Compara | Gene tree reconciliation for dating duplication events [23] | Age-dependent splice form acquisition analysis [23] |

Experimental workflows typically begin with comprehensive identification of paralogous gene pairs using sequence similarity thresholds, which allows stratification of duplicates by evolutionary age [25]. Subsequent analysis involves quantifying alternative splicing levels through metrics such as the proportion of spliced genes or the mean number of isoforms per gene [23] [25]. The relationship between gene family size and alternative splicing patterns is then analyzed while controlling for potential confounding factors including EST coverage, number of constitutive exons, selective pressure (dN/dS ratio), and transcript length [23].

Comparative Genomic Analysis Framework

A robust protocol for cross-species comparison involves calculating the Alternative Splicing Ratio (ASR) from high-quality genome annotations [22]. This approach involves:

- Genome Annotation Processing: Utilizing standardized annotation files (e.g., from NCBI) to map all transcribed coding sequences to genomic coordinates [22]

- ASR Calculation: Computing the average number of distinct transcripts generated per coding sequence across the entire genome [22]

- Normalization Application: Deriving ASR* values to account for annotation-related biases and differences in sequencing depth or tissue diversity [22]

- Phylogenetic Comparison: Analyzing ASR values across diverse taxonomic groups to identify evolutionary patterns [22]

This methodology revealed that alternative splicing rates are highly variable across lineages, with the highest levels observed in genomes containing approximately 50% intergenic DNA, suggesting an important relationship between non-coding genomic architecture and splicing complexity [22].

Functional and Evolutionary Consequences for GRN Diversification

Network Architecture and Regulatory Complexity

The interplay between gene duplication and alternative splicing has profound implications for the evolution of gene regulatory networks. GRNs generally approximate a hierarchical scale-free network topology, characterized by few highly connected nodes (hubs) and many poorly connected nodes nested within a hierarchical regulatory regime [7]. This architecture evolves through preferential attachment of duplicated genes to more highly connected genes, with natural selection favoring networks with sparse connectivity [7].

Gene duplication and alternative splicing contribute to GRN evolution through two primary mechanisms: changing network topology by adding or subtracting nodes (genes) or entire modules, and altering the strength of interactions between nodes through modifications to regulatory sequences [7]. A key example is the Drosophila Hippo signaling pathway, which operates as a conserved regulatory module that controls both mitotic growth and post-mitotic cellular differentiation depending on network context [7].

Expression Specialization and Tissue Diversification

Recent evidence indicates that expression specialization, typically coupled with functional specialization, represents the predominant evolutionary fate for both paralogous genes and alternative isoforms throughout animal evolution [27]. This specialization enables genes with ancestrally ubiquitous expression to evolve tissue-specific functions without compromising their ancestral roles in other cell types.

The acquisition of novel splice forms in duplicated genes follows an age-dependent pattern, with an estimated rate of 2.6 × 10^(-3) new splice forms per gene per million years [23]. This progressive gain of splice variants facilitates functional innovation while maintaining ancestral functions, contributing to the increasing complexity of gene regulatory networks in vertebrate evolution. The independent evolution of alternative splicing in paralogs allows for the tissue-specific subfunctionalization of duplicated genes, expanding the regulatory capacity of GRNs without increasing gene number [27].

Gene duplication and alternative splicing represent complementary rather than interchangeable evolutionary mechanisms for GRN diversification. While early studies suggested a simple anticorrelation, contemporary research reveals a more nuanced relationship characterized by temporal dependency and functional specialization. Gene duplication provides the raw material for innovation through created genetic redundancy, while alternative splicing enables rapid functional diversification through regulatory plasticity. The interplay of these mechanisms—mediated through the divergent evolution of splicing regulatory elements like ESEs and ESSs—facilitates the expression specialization necessary for the evolution of complex tissue types and specialized biological functions. Future research integrating single-cell transcriptomics with comparative genomics will further elucidate how these evolutionary drivers shape the intricate architecture of gene regulatory networks across metazoan evolution.

Computational Methods and Tools for GRN Reconstruction and Comparison

Leveraging Single-Cell Multi-Omics for Cell-Type-Specific GRN Inference

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) are fundamental mathematical representations of the complex interactions between molecular regulators—primarily transcription factors (TFs), their target genes (TGs), and cis-regulatory elements (REs) such as enhancers and promoters—that collectively determine cellular identity and function [29] [30]. The ability to infer these networks is crucial for understanding the mechanistic underpinnings of cellular processes in development, homeostasis, and disease. The field of GRN inference has evolved dramatically from its origins with microarrays and bulk sequencing technologies, which could only profile averaged signals across heterogeneous cell populations. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) first enabled the exploration of cellular heterogeneity. Now, the emergence of single-cell multi-omics technologies, which allow for the simultaneous profiling of multiple molecular layers (such as transcriptomics and epigenomics) from the same cell, has ushered in a new era [30]. Techniques like SHARE-seq and 10x Multiome generate paired data—scRNA-seq alongside scATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing)—providing an unprecedented, high-resolution view into the regulatory state of individual cells [31] [30]. This technological leap has subsequently driven the development of sophisticated computational methods designed to leverage these linked data types to infer more accurate and cell-type-specific GRNs, moving beyond the limitations of single-modality analyses [32] [30].

Methodological Foundations for GRN Inference from Multi-Omics Data

Computational methods for inferring GRNs from single-cell multi-omics data are built upon diverse statistical and machine learning foundations. Understanding these core principles is key to selecting and applying the appropriate tool for a given biological question. The following diagram categorizes the primary methodological frameworks and their relationships.

Each framework possesses distinct strengths. Regression models establish linear relationships between regulators and target genes, offering high interpretability [30]. Probabilistic models explicitly account for noise and uncertainty inherent in single-cell data, providing confidence estimates for predicted interactions, as seen in PMF-GRN [33]. Deep learning models, such as those used in LINGER and scTFBridge, capture complex, non-linear relationships but often require large amounts of data and can be less interpretable without specialized techniques [31] [34] [30]. Finally, approaches focusing on modularity and combinatorial regulation, like cRegulon and scMFG, aim to identify reusable functional units within larger networks, which can simplify the biological interpretation of the results [35] [36].

Comparative Analysis of Leading Computational Methods

The following table summarizes the key features and experimental backing of several state-of-the-art methods designed for GRN inference from single-cell multi-omics data.

| Method | Core Computational Framework | Key Innovation | Reported Performance (vs. Baseline) | Cell-Type-Specific Output | Key Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LINGER [31] | Lifelong learning neural network | Incorporates atlas-scale external bulk data as prior knowledge via elastic weight consolidation. | 4x to 7x relative increase in accuracy (AUPR/AUC) on PBMC data. | Yes (population, type, and cell-level) | ChIP-seq ground truth (AUC); eQTL consistency (AUC). |

| scMTNI [37] | Multi-task graph learning / Probabilistic graphical model | Infers GRN dynamics across cell lineages using multi-task learning. | Accurate inference on reprogramming/hematopoiesis datasets; superior to existing methods. | Yes (for each cell type on a lineage) | Evaluation on simulated data and real datasets using AUPR, F-score. |

| PMF-GRN [33] | Probabilistic matrix factorization with variational inference | Infers latent TF activity and provides well-calibrated uncertainty estimates for interactions. | Outperformed Inferelator, SCENIC, Cell Oracle on AUPRC in yeast and BEELINE benchmarks. | Yes | AUPRC against database-derived gold standards; uncertainty calibration. |

| cRegulon [36] | Combinatorial optimization & matrix factorization | Models reusable TF combinatorial modules (cRegulons) as fundamental regulatory units across cell types. | Superior in identifying TF modules and annotating cell types vs. existing methods on simulated and mixed cell line data. | Yes (annotates cell types by cRegulons) | Application to in-silico simulation and real mixed cell line data; capture of hallmark TFs. |

| scTFBridge [34] | Disentangled deep generative model | Integrates TF-motif binding knowledge to align shared embeddings across omics layers. | Identifies cell-type-specific susceptibility genes and distinct regulatory programs. | Yes | Explainability methods to compute regulatory scores for REs and TFs. |

Performance and Validation Insights

- LINGER's Accuracy Leap: The reported 4-7 fold improvement in accuracy by LINGER is benchmarked against methods that use only the single-cell multiome data itself (e.g., correlation, simple neural networks) [31]. This highlights the profound impact of integrating large-scale external knowledge to overcome the challenge of limited independent data points in single-cell experiments.

- PMF-GRN's Uncertainty Quantification: A distinctive feature of PMF-GRN is its provision of uncertainty estimates for each predicted TF-target gene interaction [33]. This is invaluable for researchers, as it allows for prioritization of high-confidence interactions for downstream experimental validation, effectively managing the risk of false positives.

- cRegulon's Biological Insight: By focusing on combinations of TFs (TF modules), cRegulon moves beyond one-to-one regulatory relationships to model the collaborative nature of gene regulation [36]. This approach successfully identified known cooperative TF complexes, such as the pluripotency regulators Sox2, Nanog, and Pou5f1, demonstrating its ability to recover biologically validated regulatory units.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for GRN Inference and Validation

A standard workflow for inferring and validating GRNs from single-cell multi-omics data involves several critical stages, from data preprocessing to experimental confirmation. The workflow below outlines the process from raw data to biological insights.

Key Protocol Steps

- Data Preprocessing: Raw data from platforms like 10x Multiome must undergo rigorous preprocessing. For scRNA-seq data, this includes normalization (e.g., using SCTransform or log-transformation) and the selection of highly variable genes [35]. For scATAC-seq data, steps involve binarization, normalization, and the selection of highly variable peaks [35]. Accurate cell type annotation, often derived from scRNA-seq clustering and marker gene expression, is a critical prerequisite for cell-type-specific GRN inference [31] [29].

- Method Application and Execution: The choice of method dictates the specific input requirements and execution protocol. For instance:

- LINGER Protocol: The method requires a count matrix of gene expression and chromatin accessibility alongside cell type annotations. Its unique lifelong learning protocol involves first pre-training a neural network on large-scale external bulk data (e.g., from ENCODE) and then refining it on the single-cell data using elastic weight consolidation (EWC) to preserve knowledge from the bulk prior. Regulatory strengths are then extracted using Shapley values from the trained model [31].

- PMF-GRN Protocol: This method uses variational inference to decompose the single-cell gene expression matrix into latent factors representing TF activity and TF-target gene interactions. A key input is a prior matrix derived from sources like TF motif databases or chromatin accessibility data, which guides the inference. The output includes the mean and variance of the posterior distribution for each interaction, representing its strength and uncertainty, respectively [33].

- Computational Validation: Before experimental follow-up, inferred networks must be computationally validated against orthogonal gold standards. Common benchmarks include:

- TF-Target Validation: Using chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) datasets for specific TFs in relevant cell types as a ground truth to calculate performance metrics like Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) [31].

- Cis-Regulatory Validation: Comparing predicted RE-to-TG links with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data from resources like GTEx or eQTLGen to assess biological consistency [31].

- Performance on Synthetic Data: Evaluating the method on simulated datasets where the true network is known, allowing for precise calculation of accuracy and false positive rates [33] [36].

- Downstream Biological Interpretation: Validated GRNs are mined for biological insight. This includes identifying driver TFs for specific cell states or diseases by correlating TF activity with case-control gene expression data [31], integrating GWAS hits to interpret the function of non-coding disease-associated variants [31] [36], and performing gene set enrichment analysis on the targets of key regulons to uncover affected biological pathways [38] [36].

Successful GRN inference relies on a suite of computational tools and curated biological databases. The following table details key resources.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in GRN Inference | Relevant Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Multiome | Wet-lab Protocol | Simultaneously generates paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data from the same single cell. | All methods (LINGER, scMTNI, etc.) [31] [35] |

| ENCODE Project Data | Bulk Reference Database | Provides atlas-scale bulk RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and ChIP-seq data across diverse cell types used as external prior knowledge. | LINGER [31] |

| Cis-Target Databases | Motif Database | Collections of TF binding motifs and conserved regulatory sequences used to link TFs to regulatory elements. | SCENIC+, cRegulon, PECA [36] [29] |

| ChIP-seq Datasets | Validation Dataset | Provides high-confidence, direct physical evidence of TF binding to specific genomic locations, serving as a gold standard for validation. | LINGER, PMF-GRN [31] [33] |

| eQTL Data (GTEx, eQTLGen) | Validation Dataset | Links genetic variants to gene expression, providing independent evidence for regulatory relationships between REs and TGs. | LINGER [31] |

| BEELINE Framework | Benchmarking Toolkit | A suite of synthetic and real datasets with curated gold standards for systematic benchmarking of GRN inference methods. | PMF-GRN [33] |

The advent of single-cell multi-omics technologies has fundamentally transformed the field of gene regulatory network inference, enabling the deconvolution of regulatory mechanisms at an unprecedented cell-type-specific resolution. As this comparative analysis demonstrates, modern computational methods like LINGER, PMF-GRN, and cRegulon leverage diverse and sophisticated frameworks—from lifelong learning and probabilistic modeling to combinatorial optimization—to deliver networks of increasing accuracy and biological relevance. The integration of large-scale external data, the provision of uncertainty estimates, and a focus on combinatorial regulation represent significant methodological advancements.

Looking forward, several challenges and opportunities will shape the next generation of GRN inference tools. A primary challenge remains the effective integration of additional data modalities, such as single-cell Hi-C for 3D chromatin structure and single-cell ChIP-seq for direct TF binding, to build even more comprehensive and three-dimensional models of regulation [30]. Furthermore, scaling these methods to the size of emerging human cell atlases, which encompass millions of cells, while maintaining computational efficiency is a pressing need [36]. Finally, improving the interpretability of complex deep learning models and linking inferred networks more directly to actionable hypotheses for drug development will be crucial for translating these computational predictions into tangible therapeutic insights for researchers and drug development professionals. The continued synergy between cutting-edge sequencing technologies and innovative computational algorithms promises to further illuminate the intricate regulatory codes that govern cellular identity and fate.

Understanding the dynamics of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) across various cellular states is fundamental for deciphering the mechanisms that govern cell behavior, development, and disease progression [39] [40]. Developmental GRNs causally link genomic regulatory sequences to dynamic developmental processes, explicitly outlining the instructions for spatial and temporal expression of regulatory genes [41]. However, current methods for comparing GRNs across different cell states or types often focus on simple topological information, such as node degree, providing only a shallow understanding of the complex regulatory mechanisms [39] [40]. This limitation is particularly pronounced in developmental biology, where regulatory dynamics drive intricate processes of cell specification and patterning.

The emergence of role-based embedding methods represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, enabling researchers to capture multi-hop topological information that extends beyond direct neighbor relationships. Gene2role, the first method to apply role-based graph embedding approaches specifically to signed GRNs (where edges denote activation or inhibition), addresses this critical gap by leveraging frameworks from established algorithms like struc2vec and SignedS2V [39] [40]. This approach allows genes from separate networks to be projected into a unified embedding space, facilitating nuanced comparisons of topological similarities across networks and developmental stages.

Methodological Framework: The Gene2role Approach

Core Algorithmic Principles

Gene2role operates on a sophisticated conceptual framework that consists of three major components: network construction, embedding generation, and downstream analysis [39]. The method specifically handles signed GRNs, represented as G = (V, E+, E-), where V denotes the set of genes, E+ represents positive (activating) interactions, and E- represents negative (inhibitory) interactions [40].

The algorithm begins by capturing topological nuances of each gene through its signed-degree vector d = [d+, d-], where d+ and d- are the positive and negative degrees, respectively [40]. This initial representation maps each gene from the signed GRNs to a point on a two-dimensional plane, establishing the foundation for more complex topological comparisons.

A key innovation in Gene2role is the Exponential Biased Euclidean Distance (EBED) function, which quantifies topological similarity between genes while accounting for the scale-free nature of GRNs [40]. The EBED function applies a logarithmic transformation to mitigate the effects of the power-law distribution of node degrees, computes the Euclidean distance, and then applies an exponential function to preserve the original proportionality of distances [40]. This sophisticated distance metric enables more accurate comparisons of gene topological roles within and across networks.

Multi-Layer Graph Construction and Embedding Learning

Gene2role constructs a multilayer weighted graph that encodes topological information between genes at various neighborhood depths [39]. For each layer k (> 0), the weight wk(u,v) for a link between gene u and gene v is computed as wk(u,v) = e^{-fk(u,v)}, where fk(u,v) represents the k-hop topological similarity between genes [40]. This multilayer approach enables the capture of both local and global topological patterns, extending the analysis beyond immediate neighbors to encompass the broader network architecture.

The embedding learning process adopts the struc2vec framework, which facilitates the projection of genes from diverse networks into a unified space [39] [40]. This unified representation is crucial for comparative analysis, as it allows researchers to directly compare topological roles of genes across different developmental stages, cell types, or experimental conditions.

Experimental Design and Benchmarking Protocol

To validate its performance, Gene2role was evaluated on GRNs constructed from four distinct data sources, ensuring comprehensive assessment across different network types and biological contexts [39] [40]:

- Simulated Networks: A simple simulated network comprising 31 genes was constructed to mimic the scale-free characteristics of biological GRNs [40].

- Manually Curated Networks: Four curated developmental networks—hematopoietic stem cell (HSC), mammalian cortical area development (mCAD), ventral spinal cord (VSC), and gonadal sex determination (GSD)—containing between 5 and 19 genes were downloaded from the BEELINE benchmark [40].

- Single-cell RNA-seq Networks: Cell type-specific GRNs were constructed from human glioblastoma data (0-h and 12-h stages), human bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMC), and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) using EEISP and Spearman correlation methods [40].

- Single-cell Multi-omics Networks: Networks were obtained from CellOracle, integrating scRNA-seq and sci-ATAC-seq data from differentiating mouse myeloid progenitors across 24 cell states [40].

Baseline Methods and Evaluation Metrics

Gene2role was compared against several baseline approaches to establish its performance advantages [39]. The comparative analysis included:

- Traditional topological methods focusing on direct gene connections and simple degree-based metrics

- Proximity-based graph embedding approaches commonly used in GRN analysis

- Other role-based embedding methods not specifically designed for signed networks

Evaluation was conducted using multiple metrics assessing the quality of embeddings for capturing topological similarities, the accuracy in identifying differentially topological genes, and the effectiveness in quantifying gene module stability across cellular states [39].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Results

Topological Representation Accuracy

Table 1: Performance Comparison in Capturing Topological Nuances

| Method | Network Types Supported | Multi-hop Connectivity | Signed Edge Support | Cross-Network Comparability | Developmental GRN Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene2role | Signed GRNs | Extensive (k-hop neighborhoods) | Native support | Unified embedding space | Directly demonstrated [39] [40] |

| Traditional Topological Methods | Unsigned/Signed GRNs | Limited (0-1 hop) | Partial | Limited | Indirect application [39] |

| Proximity-based Embeddings | Primarily unsigned | Limited | Not supported | Separate spaces per network | Not specialized [40] |

| struc2vec | Unsigned networks | Extensive | Not supported | Unified embedding space | Requires adaptation [39] |

| SignedS2V | Signed networks | Moderate | Native support | Limited | Not specifically designed [39] |

Gene2role demonstrated superior performance in capturing intricate topological nuances of genes across all four network types [39] [40]. The method effectively quantified topological similarities by considering both direct connections and broader neighborhood topologies, outperforming methods that focus solely on direct topological information [40].

Application-Specific Performance

Table 2: Performance in Downstream Analysis Tasks

| Analysis Task | Gene2role Performance | Traditional Methods Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of Differentially Topological Genes (DTGs) | Effectively identified genes with significant topological changes across cell types/states [39] | Limited to expression or simple topological changes | Provides perspective beyond differential expression [39] |

| Gene Module Stability Analysis | Precisely quantified stability of gene modules between cellular states [39] | Limited to co-expression or functional enrichment | Measures topological preservation of modules [40] |

| Cross-Network Comparison | Successfully projected genes from separate networks into closely positioned spaces [40] | Required separate analyses with manual integration | Enables direct comparison of topological roles [40] |

| Developmental Process Tracking | Capable of tracking topological role changes during differentiation [40] | Focused on expression changes only | Links structural and functional changes in development |

The application of Gene2role to integrated GRNs enabled identification of genes with significant topological changes across cell types or states, providing insights beyond traditional differential gene expression analyses [39]. Additionally, the method successfully quantified the stability of gene modules between cellular states by measuring changes in gene embeddings within these modules [39].

Research Reagent Solutions for GRN Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function in GRN Analysis | Example Use in Gene2role Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| BEELINE Benchmarks | Provides standardized GRNs for method comparison [40] | HSC, mCAD, VSC, and GSD networks for validation [40] |

| CellOracle | Infers GRNs from single-cell multi-omics data [40] | Source of single-cell multi-omics networks [40] |

| EEISP | Constructs GRNs from scRNA-seq data based on co-dependency [40] | Generated cell type-specific GRNs from glioblastoma data [40] |